Vancouver Island Indigenous Information

- …

Vancouver Island Indigenous Information

- …

Vancouver Island Indigenous Information

Definitions of Colonization, Decolonization, Equality vs Inclusion, Reconciliation, Cultural Appropriation and information about Residential Schools & the 60's Scoop, and the trauma the Candian Government inflicted upon Indigenous People in Canada

Learn about Cultural Appropriation of Indigenous Art on Orange Shirt Day

What does Reconciliation mean to me?

Reconciliation to me involves a lot of different aspects. Reconciliation is creating a better country for everyone, so that Indigenous people in many places across the country are no longer living in third world conditions in a first world country.

- It means equal human rights, living conditions, representation in all aspects, government, politics, court, and media.

- It means acknowledging the past and creating a better future, where we acknowledge Indigenous peoples' history long, long, long before any settlers came to Canada. Indigenous peoples’ history spans millennia, and acknowledging that means acknowledging their science and history, and it being equally valued, taught and used in scientific environments, as well as in our efforts for climate change.

- It means giving them control over their own lands and recognizing that they have a much deeper understanding of the lands across Canada than settlers do.

- It means respecting and acknowledging self-governance and working alongside and with each other. It means Indigenous cultures and languages revitalized and spoken fluently, passed on intergenerationally, and equally respected and valued.

- It means two-eyed seeing, using two ways of being, thinking, and doing together, taught together and always considered together in all decision making, without the Western way ever being valued or respected as more important. It means having an equal power balance in our country.

- It means capitalism no longer running our country but seeing society and land as both equally important. It means creating a land-based worldview that respects and values everyone, without racism or discrimination that puts down and targets specific parts of the population. Even if there are different social classes, these are not only reserved largely for certain segments of the population, and everyone contributes equally, government and society does not favour the rich and powerful more than others in the society, as those with more money share to better the entire society, instead of keeping a power imbalance of 1%.

Reconciliation is about addressing the harms and injustices of the past and actively working, in all parts of society, to repair all of the wrongs that the settler government has inflicted, that not only affect Indigenous people but also non-Indigenous people. Therefore, it means creating a better, healthier country for every single person in this country, where everyone lives better lives than the current colonial systems in Canada allow.What am I doing to move forward in my own reconciliation journey?

I have taken 2 Certificates from 4 Seasons of Indigenous Learning and Reconciliation from First Nation's University of Canada to learn more about reconciliation and decolonization. I am working on my Certificate for Indigenous Community Language Planning from Canadian Languages and Literacy Development Institute (CILLIDI) from University of Alberta, which is a career path I wish to pursue. I also took BC First People and BC First People English in Grade 12 at SelfDesign Learning Foundation, to also learn more about reconciliation and decolonization. .

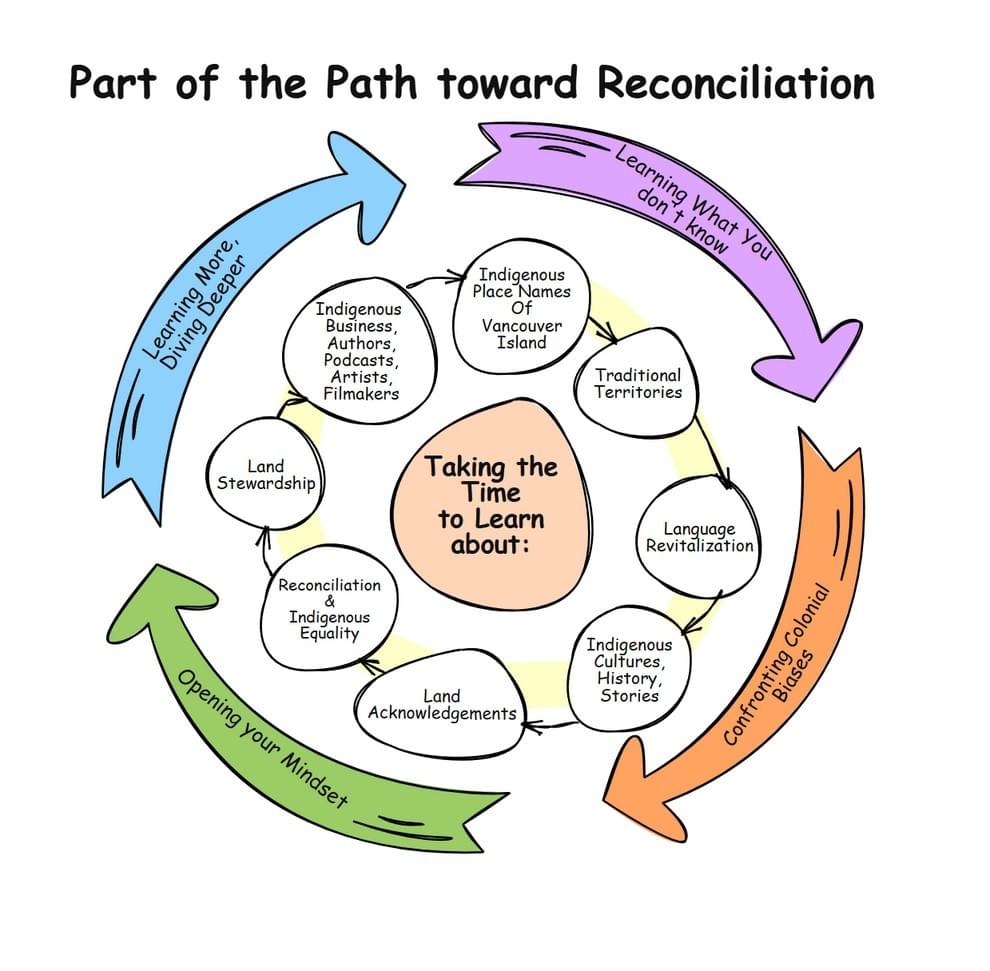

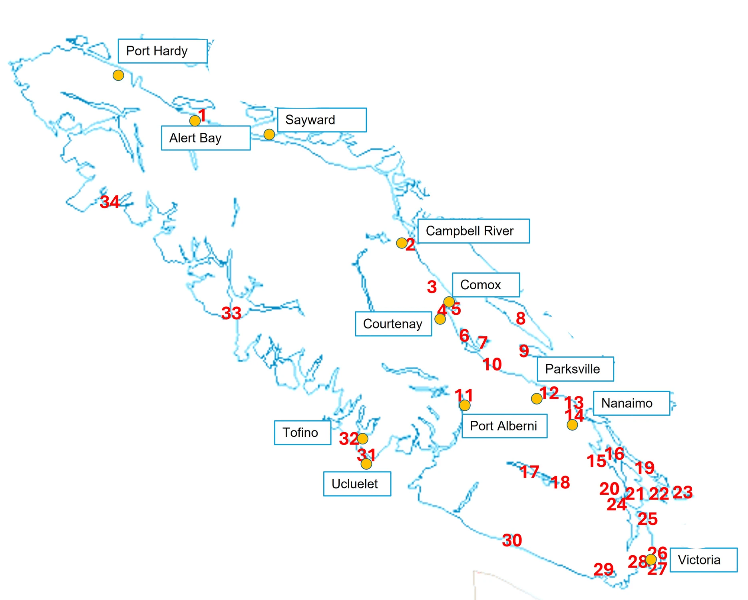

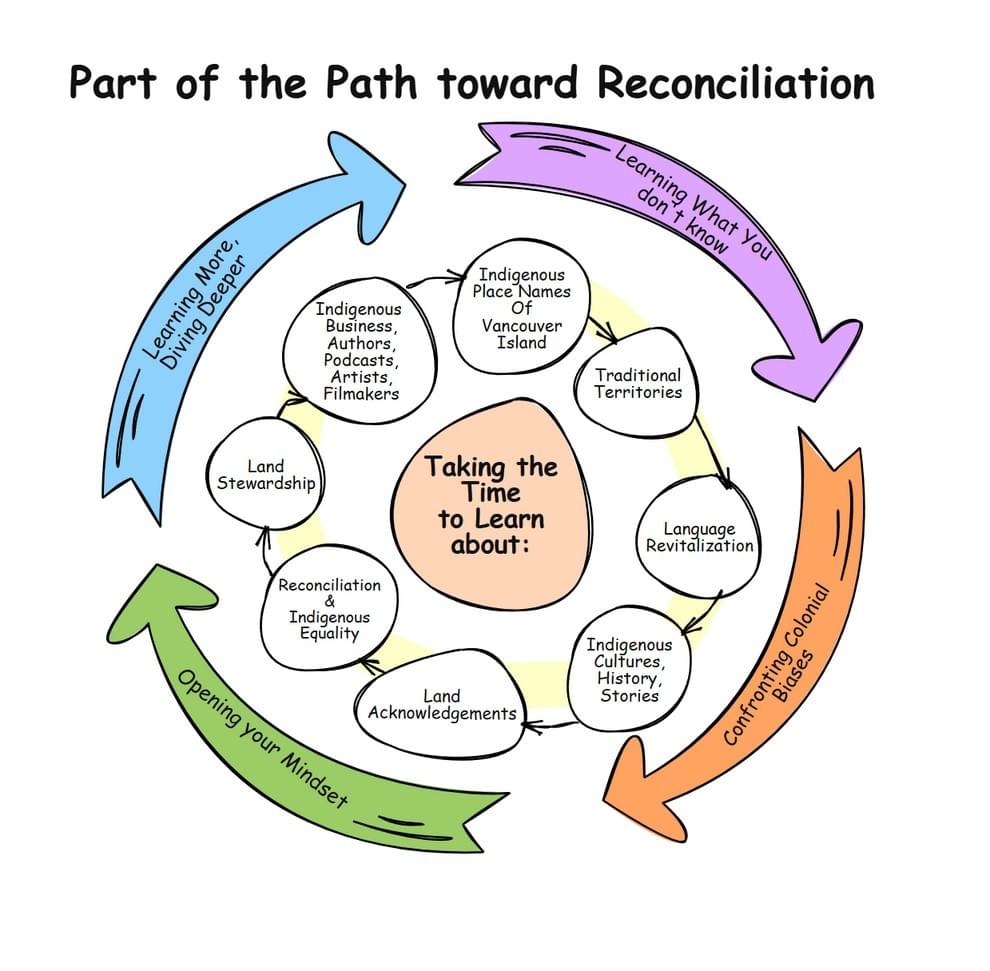

I applied for an was accepted into the DWF Youth Ambassador Program in 2025 to learn more about reconciliation and decolonization. The Vancouver Island Place Names Brochure that I created as part of the ReconciliACTION project, is a resource that local people and tourists to the Island can pick up from gas stations, gift shops, coffee shops, tourist information booths, and museums, to learn more about the Indigenous people of Vancouver Island and the unceded territories that they live on. The more we learn, the more we understand, the more we care and the more we try to fix a broken system.

The QR code on the brochure links to this website, where people can continue their learning on the Indigenous languages that are listed on the map and find out more information about the Indigneous people who speak these languages, their history, culture, traditions, stories, territories, and land stewardship principes they have been practicing since time immemorial. (Note: This brochure and website are not sponsored or approved by any Indigenous Nations or people on Vancouver Island. I have created this brochure and website as my own process or reconciliation.)

I hope the learning in the brochure and on this website inspires you to do more research on the Indigenous people of Vancouver Island and begin your own reconciliation and ReconciliACTION journey. I invite you to visit the links to Indigenous businesses, authors, film makers and artist found in the resources section on the site, and I hope that it inspires you go further in your own research on the destructive history, laws and polices that the government of Canada and the provinces had and still have towards Indigenous Canadians.

Colonization

What is Colonization?

Definitions

Colonization in Canada

"In Canada, colonization occurred when a new group of people migrated to North America, took over and began to control Indigenous Peoples. Colonizers impose their own cultural values, religions, and laws, make policies that do not favour the Indigenous Peoples. They seize land and control the access to resources and trade. As a result, the Indigenous people become dependent on colonizers.

Today many Indigenous people still struggle, but it is a testament to the strength of their ancestors that Indigenous People are still here and are fighting to right the wrongs of the past.

Before the arrival of European explorers and traders, Indigenous Peoples were organized into complex, self-governing nations throughout what is now called North America. In its early days, the relationship between European traders and Indigenous Peoples was mutually beneficial. Indigenous Peoples were able to help traders adjust to the new land and could share their knowledge and expertise. In return, the traders offered useful materials and goods, such as horses, guns, metal knives, and kettles to the Indigenous Peoples. However, as time went by and more European settlers arrived, the relationship between the two peoples became much more challenging.

The myth of terra nullius

European map-makers drew unexplored landscapes as blank spaces. Instead of interpreting these blank spaces as areas yet to be mapped, they saw them as empty land waiting to be settled. When settlers arrived in North America, they regarded it as terra nullius, or “nobody’s land.” They simply ignored the fact that Indigenous Peoples had been living on these lands for thousands of years, with their own cultures and civilizations. For the settlers, the land was theirs to colonize. As time went on, more and more settlers took over the traditional territories of Indigenous Peoples.

Changing names and rewriting history

The settlers began to give their own names and descriptions to the land they had “discovered.” For example, Vancouver and Vancouver Island are named after Captain George Vancouver, who was born in England in 1757, and not after a hereditary Chief of the territory, whose family had lived in the area since the beginning of time. The land, landmarks, bodies of water and mountain ranges already had names, given to them by Indigenous Peoples. Settlers did not learn these names and made their own names for landmarks, mountains, bodies of water and regions instead. This was one of the ways in history was rewritten to excluded Indigenous Peoples contributions and presence."

How Colonization has impacted Indigenous People in Canada

- Information by Indigneous Corporate Training

"Eight of the key issues of most significant concern for Indigenous Peoples in Canada are complex and inexorably intertwined - so much so that government, researchers, policymakers and Indigenous leaders seem hamstrung by the enormity of these issues. It is hard to isolate one issue as being the worst. The roots of these issues lie in the Indian Act and colonialism. Canadian Indigneous people still today struggle with these issues because of racism, discrimination and the presisting colonial mindset of many people and government officials in Canada.

1) Poorer health The World Health Organization's investigation into health determinants now recognizes European colonization as a common and fundamental underlying determinant of Indigenous health. There have been strides made on the part of many Indigenous communities to improve education around health issues. Still, despite these improvements, Indigenous people remain at higher risk for illness and earlier death than non-Indigenous people. Chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease are on the increase. There are definite links between income, social factors, and health. There is a higher rate of respiratory problems and other infectious diseases among Indigenous children than among non-Indigenous children - inadequate housing and crowded living conditions are contributing factors.

2) Lower levels of education

While Canada has one of the highest levels of educational attainment in the world, the rate of graduation for Indigenous students remains far lower than that of non-Indigenous students. For Indigenous students living on reserve, the gap is vast. According to a C.D. Howe Institute study, only 48 percent of students living on reserve have completed high school, while 75 percent living off-reserve have completed high school.

3) Inadequate housing and crowded living conditions

Almost one in six Indigenous people (16.4%) lived in a dwelling needing major repairs in 2021, a rate nearly three times higher than the non-Indigenous population (5.7%). In 2021, 17.1% of Indigenous people lived in crowded housing—housing not considered suitable for the number of people living there, according to the National Occupancy Standard. (In Canada many Indigenous people live in 3rd world conditions with poor to terrible housing, lack of clean water, lack of accessible healthy food, medical care, education, opportunties and rights. Many Nation have had the land around them poisoned by Industry and Mining.)

4) Lower income levels

The 2021 Census marked the first time low-income data were made available for all geographic regions in Canada, including reserves and northern areas. Of the 1.8 million Indigenous people in Canada in 2021, 18.8% lived in a low-income household, as defined using the low-income measure, after tax, compared with 10.7% of the non-Indigenous population. Among the three Indigenous groups, the low-income rate was highest among First Nations people (22.7%). It was exceptionally high among status First Nations people living on reserve, almost one in three (31.4%) of whom lived in a low-income household.

5) Higher rates of unemployment

Indigenous people have historically faced higher unemployment rates than non-Indigenous people. The higher rate of unemployment is connected to lower levels of education. Literacy and numeracy skills are the foundations for skills training and meeting the demands of an increasingly digital workforce. Other barriers include cultural differences, racism, discrimination/stereotypes, self-esteem, poverty and poor housing, no driving license, no transportation, and no child care.

6) Higher levels of incarceration

32% of federal inmates identify as Indigenous, despite only making up around 5% of the total population in Canada. Indigenous women now account for almost half of the female inmate population in federally run prisons: “On April 28, 2022, the number of incarcerated Indigenous women reached 50% for the first time (298 Indigenous and 298 non-Indigenous women in federal custody) . . . this over-representation is largely the result of systemic bias and racism, including discriminatory risk assessment tools, ineffective case management, and bureaucratic delay and inertia.”

7) Higher rates of unintentional injuries and early deaths among children and youth Unintentional injuries (accidents) are events in which there is no intent to harm. Accidents occur at disproportionately higher rates for Indigenous children and youth than for non-Indigenous youth and at a higher rate on reserves than in urban settings. Also, injured Indigenous children on remote reserves are much less likely to receive rehabilitation or other resources after being released from the hospital due to a shortage of healthcare resources in remote communities.

8) Higher rates of suicide Indigenous people in Canada have some of the highest suicide rates in the world. Suicide and self-inflicted injuries are the leading causes of death for First Nations youth and adults up to 44 years of age. For Inuit, the suicide rate is nine times the national rate; for First Nations, the suicide rate is three times the national average; and for Métis, the suicide rate is twice the national average."

The inter-generational trauma of Residential Schools has deeply impacted genrations of Indigenous people in Canada and affects almost every aspect of their lives. Learn more HERE.

Decolonization

Decolonization

Definitions

Decolonization

As defined by the Canadian Governement: No definition

British Columbia Office of Human Rights: Decolonization is central to the work of human rights in our society, and consequently to the work of BC’s Office of the Human Rights Commisioner. Decolonization is the dismantling of the process by which one nation asserts and establishes its domination and control over another nation’s land, people and culture. It is the framework through which we are working toward undoing the oppression and subjugation of Indigenous peoples in what is now known as British Columbia and unlearning colonial ways of thinking and being. To make transformative and systematic change, it is important to learn about decolonization. We are all responsible for ongoing decolonization work and together we can imagine a new reality that honours Indigenous perspectives, culture and peoples.

As defined by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Decolonization is now recognized as a long-term process involving the bureaucratic, cultural, linguistic and psychological divesting of colonial power [1]

As defined by Simon Fraser University: Decolonization means examining how academia is failing Indigenous communities and knowledge, not only in the lack of inclusion in course availability and curriculum, but also in supporting Indigenous students, staff, and faculty. Educational institutions then have a responsibility to enact transformative changes, to address these failings and move forward.

What is Decolonization:

- Information by BC Campus

What would decolonization look like?

Decolonization would mark a fundamental change in the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. It would bring an end to the settler effects on Indigenous Peoples with respect to their:

- governments

- ideologies

- religions

- education systems

- cultures

Decolonization requires an understanding of Indigenous history and acceptance and acknowledgement of the truth and consequences of that history. The process of decolonization must include non-Indigenous people and Indigenous Peoples working toward a future that includes all.

Canadian citizens must acknowledge that the Canada we know today was built on the legacy of colonization and the displacement of Indigenous Peoples. Decolonization must continue until Indigenous Peoples are no longer at the negative end of socio-economic indicators or over-represented in areas such as the criminal justice or child welfare system.

For Indigenous Peoples, decolonization begins with learning about who they are and recovering their culture and self-determination.

Many Indigenous people may have difficulty understanding different aspects of, or perspectives on, Indigenous knowledge. This process can be difficult for all of the reasons we have already discussed, and it will take time to overcome the difficulties. It must occur on many levels: as an individual, a member of a family, a community, and a Nation. It requires perseverance, support, and knowledge of culture.

The process of decolonization is a process of healing and moving away from a place of anger, loss, and grief toward a place where Indigenous Peoples can thrive. This can be overwhelming and seemingly impossible for some. It must be acknowledged that not all Indigenous Peoples are in the same place on this “decolonization journey,” but together Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous peoples can succeed.

Continuous reinforcement and rediscovery of Indigenous language, cultural, and spiritual practices empowers people to move forward in their growth as proud Indigenous citizens.

Decolonization is not

- Information by BC Campus

An attempt to re-establish the conditions of a pre-colonial North America and would require a mass departure of all non-Indigenous people from the continent.

Equality vs Inclusion

Definition of Equality: the state of being equal, especially in status, rights, and opportunities.

Definition of Inclusion:

The practice or policy of providing equal access to opportunities and resources for people who might otherwise be excluded or marginalized, such as those who have physical or intellectual disabilities and members of other minority groups.

But why is inclusion colonization?

Inclusion means to be included into the existing social structure. It is not about equality or two-eyed seeing. It is about Indigenous people being included into the colonized system with the same rights as everyone else. But that is assimilation.

Why we must decolonize our mindset?

Inclusion means to be included into the existing social structure. It is not about equality or two-eyed seeing. It is about Indigenous people being included into the colonized system, with the same rights as everyone else in the colonized system. But that is assimilation in a system. It is not about having your own system of wisdom, knowing and seeing being seen as equal and just as important as another system.

That is why we must decolonize our minds, because words like inclusion are created by colonialist societies and seem like nice things, but they are simply colonization in a nicer term.

Equality means your way and my way are equally important, even though we do things in different ways. Equality is reconciliation. Indigenous science, wisdom, inventions, knowing, land stewardship principles, controlled burning, self-governance are equally as important as Western ways of doing things. We when can listen, acknowledge the truth in what Indigenous people have to say, not try to take it make it our own or assimilate it into our culture, but say this came from Indigenous people and it is their way and it is a better way for us to do things and we want to do it their way, then this is decolonization.

Reconciliation

Definitions of Reconciliation

Reconciliation

As defined by the Canadian Government: Building a renewed relationship with First Nations, Inuit and Métis based on the recognition of rights, respect and partnership.

As defined by the British Columbia Government: B.C. works in collaboration with Indigenous leaders, government agencies, industry, local government and the public to support reconciliation and related agreements. Reconciliation and related agreements focus on closing socio-economic gaps that separate Indigenous People from other people living in B.C. and building a province where everyone can participate in a prosperous economy. The provincial government has a number of key documents that guide the ongoing relationship with Indigenous Peoples in B.C.

As defined by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Reconciliation is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in this country. In order for that to happen, there has to be awareness of the past, an acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour.

As defined by North Island College: We recognize that our collective and individual efforts to advance the 94 Calls to Action as set out by the Truth and Reconciliation (TRC) Commission of Canada are a vital aspect of reconciliation. We will draw from the guiding principles of the TRC to build awareness of the past, acknowledge harms and atone for the causes of those harms, while taking action to change behaviours and the ongoing legacy of residential schools.

As defined by Simon Fraser University: Simon Fraser University respectfully acknowledges the Coast Salish Peoples, including the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish), səl̓ilw̓ətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh), q̓íc̓əy̓ (Katzie), kʷikʷəƛ̓əm (Kwikwetlem), Qayqayt, Kwantlen, Semiahmoo and Tsawwassen Peoples, on whose unceded traditional territories our three campuses reside.

In acknowledging all the land holders of shared territories, we take on the responsibility of reconciliation by understanding the truth and stories of these lands and the peoples’ relationships and responsibilities to these lands.

You can take action by learning more about Indigenous Peoples in B.C., exploring their visual culture and developing your positionality statement or land acknowledgement:

- Find out how SFU is advancing reconciliation

- President's statements

- Stay up to date with SFU reconciliation news

- Looking Forward... Indigenous Pathways To and Through Simon Fraser University-Final Report

- Read SFU's reconciliation reports

- Learn about residential schools in Canada

- Access learning and research resources

- Take action

What is Reconciliation

- Information by Indigenous Corporate Training

Reconciliation is:

- Critical

- Complex

- Multifaceted

- Continuous

- A process

- About working towards solidarity as a society and country

- The responsibility of every Canadian

- Honouring treaties

- Acknowledging and respecting Indigenous rights and title

- Acknowledging and letting go of negative perceptions and stereotypes

- Acknowledging the past and ensuring that history never repeats

- Learning about Indigenous history

- Recognizing the inter-generational impacts of colonization, attempts at assimilation, and cultural genocide

- Recognizing the critical roles, Indigenous Peoples have held in the creation of Canada, their contributions to world wars to protect Canada

- Taking responsibility as a person, a parent, an employee, an employer to:

- Never utter, accept, or ignore a racist comment

- Never utter, accept, or ignore a statement that includes a stereotype about Indigenous Peoples

- Respect for:

- Indigenous individuals

- Indigenous beliefs, cultures, traditions, worldviews, challenges, and goals

- Recognition and support of the deep connections Indigenous Peoples have to the land.

- Supporting the reclamation of identity, language, culture, and nationhood

- Healing for all Canadians

- Good people doing good things

- Building relationships

- Never giving up despite setbacks

- Humility

- An opportunity to move forward

- A commitment to taking a role and assuming responsibility in working towards a better future for every Canadian

Reconciliation is not

- Information by Indigenous Corporate Training

- A trend

- A single gesture, action, or statement

- A box to be ticked

- About blame

- About guilt

- About the loss of rights for non-Indigenous Canadians

- Someone else’s responsibility

How to start your own Reconciliation Journey

Information by VC Indigenous Resource Hub

"Many non-Indigenous Canadians and organizations are trying to understand how they can learn, support, act, change. We are all on a path of learning, understanding, grieving, and growing. Reconciliation and healing are complicated but there is a way to move forward, one foot in front of the other, one hand reaching out to another. This is a personal journey to increase understanding, knowledge and compassion about Canada’s history vis-a-vis Indigenous Peoples, the historical and ongoing impact this has, and how each of us can contribute to healing and reconciliation in a meaningful way. Organizations can make connections and build relationships with Indigenous people, organizations, and nations which will help build knowledge and understanding. When staff and volunteers in organizations have more knowledge and understanding, they can learn how to restructure policies and practices and begin to reduce bias and discrimination.

“Reconciliation is getting to know one another” Mary Simon, Governor General of Canada. The journey of reconciliation involves building relationships and connections with Indigenous people in our communities. Take time to get to know the Nations and Indigenous people where you live. Learn the history and current affairs of local Nations and seek opportunities to work with Indigenous organizations.

The journey of reconciliation takes time and patience. We will make mistakes and may forget that there is more than one

right way to do things, but we must continue to strive for awareness and understanding.Self-reflection and seeking understanding throughconnections and dialogue with others can help us to move toward reconciliation."

You can also begin your own reconciliation journey by reading through all the information on this website to decolonize your mindet and become aware of your own subconscious, colonial biases.

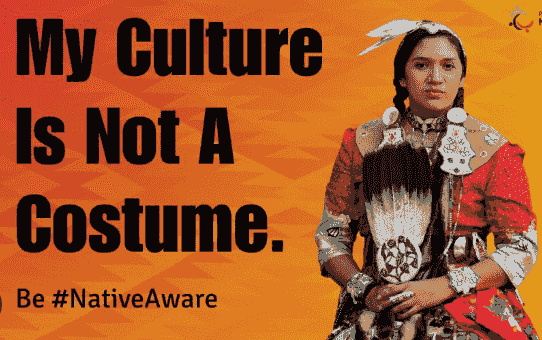

Cultural Appropriation

What is Cultural Appropriation?

"Cultural appropriation can be understood as using intellectual property, traditional knowledge, cultural expressions, or artifacts from someone’s culture without permission. It is most likely to be harmful when the source culture is a group that has been oppressed or exploited in other ways (as with Indigenous Peoples), or when the object of appropriation is particularly sensitive or sacred. However, it is not always simple to identify when cultural appropriation is occurring. Let’s explore two examples of learning experiences that use creating poles to understand the nuances of cultural appropriation.

Example 1: Cardboard Box “Totem” Poles

In the learning exchange video series “appropriation,” Susan Dion gives the example of elementary school educators having their students make “totem” poles out of cardboard boxes. She explains that this activity trivializes the importance of poles in Haida culture. Dion compares making totem poles to having children make a model of a Catholic chalice and host and pretending to give and take first communion. This would be clearly recognizable as inappropriate and offensive.

Example 2: Thunderbird/Whale Protection and Welcoming Pole: Learning and Teaching in an Indigenous World

The University of Victoria’s course, “Thunderbird/Whale Protection and Welcoming Pole: Learning and Teaching in an Indigenous World” for the faculty of education was pedagogically based in an Indigenous teaching and learning experience. The course involved the construction and installation of a thunderbird/whale house pole, and pre-service teachers, education graduate students, and faculty worked alongside an Aboriginal artist-in-residence and an Aboriginal mentor carver/educator. As part of an interactive learning community, the students experienced the principles of traditional Indigenous ways of teaching and learning including, mentorship and apprenticeship learning; learning by doing; learning by deeply observing; learning through listening, telling stories, and singing songs; learning in a community; and learning by sharing and providing service to the community.

In the first example, cultural appropriation occurred for the following reasons:

Indigenous communities that created totem poles have been exploited through colonialism in many other ways. They were not involved in the assignment to make poles, and they did not grant permission to the teacher to make poles.

Poles have a spiritual significance, which was not honoured in the activity.

The creating of the poles was not interwoven with Indigenous approaches but was a one-off assignment within a predominantly Westernized approach.

In the second example, making poles was a respectful activity for the following reasons:

Indigenous community experts were actively involved.

The activity was deeply integrated with Indigenous pedagogical approaches.

The spiritual significance of the pole was recognized by following proper protocols and values.

Cultural appropriation can feel like an ambiguous topic, and the fear of appropriating may lead educators to shy away from Indigenous content or issues. But this is not an acceptable response. Instead, what is required is that educators think through considerations of cultural appropriation carefully. They need to build connections with Indigenous communities so that they can incorporate Indigenous culture in ways that are not harmful or exploitative. This may be harder work than simply adding an Indigenous text, speaker, or activity into a course, but it is the responsibility of all educators to engage in this work."

Why is Cultural Appropriation Disrespectful?

- Information by Indigenous Corporate Training

Indigenous Peoples, their cultures, their pre-contact lives, and the impact of colonization. It is through education that people will understand that Indigenous Peoples have struggled to protect and preserve their culture, and how they were forced to change the way they lived, spoke, celebrated... As Canada moves along the reconciliation continuum, we hope that all will want to learn about Indigenous Peoples, their cultures, their pre-contact lives, and the impact of colonization . It is through education that people will understand that Indigenous Peoples have struggled to protect and preserve their culture, and how they were forced to change the way they lived , spoke , celebrated , and worshiped.

How to avoid Cultural Appropriation?

- Information by Indigenous Corporate Training

If you admire an aspect of another culture, then learn about it and purchase items directly from a person of that culture. If you like the look of Cowichan sweaters, don’t buy a “Cowichan-inspired” sweater from a retail giant, buy from a Coast Salish knitter or an Indigenous-owned store that buys sweaters directly from the knitters. That is cultural respect.

Don’t refer to a culture or a People as exotic. That emphasizes their “otherness”. To them their culture is not exotic, it’s who they are and what is important to them.

Don’t amp up or modernize aspects of another culture because by doing so suggests that the modernized rendition by a non-Indigenous entity makes it better.

Don’t assume that it’s okay to “borrow” aspects from another culture. In many Indigenous cultures, strict and ancient protocols dictate who can sing certain songs, perform certain dances, and tell certain stories. We don’t just take from one another.

“Borrowing” from another culture is symptomatic of the history of colonialism in which the dominant/colonizing culture assumes everything from the colonized culture is there for the taking. And that’s been a pattern in the history of this country.

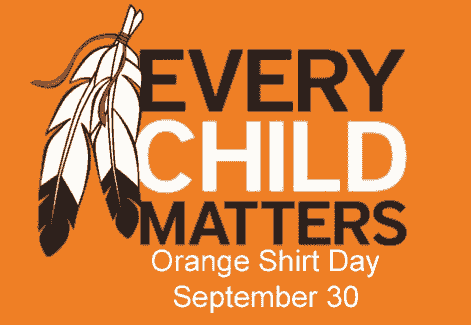

Orange Shirt Day

September 30 - Truth and Reconciliation day and Orange Shirt Cultural Appropriation

by Chelsey Petr

"September 30th is Truth and Reconciliation Day and to honor it, people wear orange shirts. This day is one of remembrance, reconciliation, awareness, education and healing from the horrors that were the residential schools and colonization. Indigenous children were forced into Residential Schools and faced with inhuman treatment and abuse that ended with thousands of Indigenous children dying in those schools and many more ending up with lifelong trauma. This is a horror in Canada's past that deserves to be remembered and taught about, so that it may never happen again. In order to remember and work towards reconciliation, Orange Shirt Day was created.

Orange Shirt Day, named after First Nation's woman, Phyllis Webstad, from Stswecem’c Xgat’tem peoples, was created inremembrance of Phyllis Webstad's Orange shirt that was taken awayfrom her, when she first entered the residential school system. It was given to her by her grandmother and then was taken from her forcibly. “I never wore it again. I didn’t understand why they wouldn’t give it back to me, it was mine! The color orange has always reminded me of that and how my feelings didn’t matter, how no one cared and how I felt like I was worth nothing,” said Webstad. “All of us little children were crying and no one cared.”

This story is one that reminds us of what terrible things occurred in those schools, and how inhuman it was. Now, the orange shirt is a sign for healing, truth and reconciliation. It has become a world wide symbol, and the story behind the orange shirt, as well as the residential school children's truths, will not be forgotten.

In BC, the Orange shirt has become more than just a symbol or a certain shirt to wear on a certain day. It has become a

way to bring the community, especially youth, together to learn and remember the residential schools in an artistic way that will stick with them for a lifetime. "How Cultural Appropriation is affecting Orange Shirt Day

"First Nations artists have been designing orange shirts for Orange Shirt day, since it was recognized in 2013, with unique and heartfelt designs that honor their culture, the children whose lives were lost, and the survivors. Their art aims to help heal their community and the sale of the shirts raises funds for traditional healing centers. However, as people and corporation on mass have started buying orange shirts to commemorate Truth and Reconciliation Day, large clothing manufacturing, silkscreen printing corporations and webpages looking for a profit, have taken notice. First Nations artists have begun seeing their artwork and designs appear on websites and Facebook pages without their consent or knowledge, and without any credit or recognition for the Orange Shirt cause. (Lupton) One First Nations artist, Hawlii Pichette, spoke out to CBC news about the theft of First Nation's art, when she saw her designs being sold on a Facebook page without her permission or knowledge. Even after filling out 6 web reports on intellectual property violations that it washer work, the company kept selling t-shirts with her art on them. "They're not just stealing artists' work; they're actually appropriating culture," Hawlii Pichette told CBC news, about the companies profiting off of stolen art. "They're making money off of our trauma."

Another First Nations artist, Andy Everson, noticed a bunch of Facebook ads promoting orange shirts, which are profiting off of the day, as well as stolen First Nations art. These ads and pages don’t give any credit or information about the day. They aretaking advantage of the very purpose of the orange shirts, which is to raise awareness about Truth and Reconciliation. “To capitalize on such a devastating part of our history is unconscionable”, Andy Everson stated.

To fight the problem, First Nations artists have been sharing their stories to news pages and websites about what has been happening and how these unethical companies are using Truth and Reconciliation Day for profit. First Nations artists have also been promoting preferred websites on media channels, sharing where you can buy legitimate orange shirts from First Nations and non-profit artists and companies.

Where you buy your orange shirt matters — here's why!

Phyllis Webstad, the creator of Orange Shirt Day, also shared how the Orange Shirt Society is fighting against these companies. The Orange Shirt Society is now adding copyright to their website, which will help them prove to a lawyer or a court of law that the art and slogan belongs to them, and that it can not be used without their expressed knowledge or

permission. They have also put in an application to trademark “Every Child Matters”, so that it cannot be printed or used without the Societies expressed permission. “If we are successful receiving the trademark for Every Child Matters, we will then be able to draft and send out to these companies a cease and desist letter, but until then we really can’t do much, especially the ones in the other countries,” Phyllis Webstad said. A trademark gives the Society much stronger legal basis to go after companies that are trying to capitalize on the Every Child Matters message, and hopefully, these opportunistic companies will think twice before trying to steal this important Truth and Reconciliation theme.However, as Phyllis Webstad said, it’ll be hard to fight against companies in countries outside of Canada that are stealing and selling shirts with First Nations art. While trademarking the Every Child Matters slogan begins the quest to be able to fight these profiteering companies in court, that can only get most societies or artists so far. With many countries having their own trademarking laws, it is going to be very hard and expensive to not only trademark the slogan in each of those countries, but also to sue companies in those countries, who violate the trademark and copyright art and slogan.

How do Individuals and Corporations stop the theft of First Nation's art?

To further try and stop the theft of First Nation’s art and stop profiteering companies, I think that educating people, much like the artists and the Orange Shirt Society have been doing, by sharing approved websites for purchasing shirts, is a good way to begin. However, I think that it has to go beyond just the artists and the First Nations societies trying to educate people, it needs to be led by the federal government, provincial governments, and local chamber of commerce business associations; to have a larger and stronger educational message about what is appropriate for this day and how to purchase appropriate merchandise from reputable companies.

I believe the problem right now is that most people and organizations don’t know how to honor this day properly because there has not been a coordinated educational effort put out by the governments. Most people and businesses have the right intention, but don’t know the proper places to go and find First Nations approved orange shirts. I believe that because this is a fairly new federally regulated day, over time Canadian businesses and the general public will get better with honoring this day appropriately, but in the meantime there is much hurt and anger that is being caused, simply because some people only care about profit, over ethics. "

Where should individuals and corporations purchase shirts for September 30?

When purchasing orange shirts, look for merchants that support Indigenous causes. Avoid buying from random sellers on platforms like Etsy and Amazon, as they may not benefit Indigenous communities. Choosing products from official retailers and Indigenous artists ensures your purchase aids healing and truth-telling efforts. You can go to the Orange Shirt Society page and find a list of approved merchants.

By Renee Petr

Residential "Schools"

For a period of more than 150 years Indigenous, Inuit and Métis children were forcibly taken by the RCMP and Catholic priests from their families and communities to attend residential "schools", which were often located far from their homes. Most children were not able to come home for months and months at a time, some even years at a time. Their language, culture, identity, pride and self-confidence were stripped from them and beaten out of them. They where beaten for speaking their language, their hair was cut, brothers and sisters were not allowed to see each other, and many children were forced to endure physical, mental and sexual abuse. The children were starved, tested upon, used as free labour and given mouldy food in very meager portions. Many children starved to death. The schools were cold, drafty, void of love and kindness, and many children became very sick and many died. Residential "Schools" were the Canadian Governments solution to the "Indian Problem" and the idea to get rid of the Indian in them and assimilate them into White culture or the children would die during the process.

When these traumatized children returned to their communities, they could not speak their language, communicate with their families and were ashamed of their culture and way of life. More than 150,000 children attended Indian Residential "Schools" and many never returned. Indian Residential Schools were compulsory for Treaty-status children between the ages of 7 and 15, but many were taken away from their families at the age of 4 or 5. If the parents fought to keep their children home, they were imprisoned. Because Residential "Schools" existed for 150 years in Canada, the deep and lasting inter-generational trauma that generations of Indigenous people have had to endure, has created many terrible impacts for the people, their children, their culture, languages, ceremonies, identity, well being and identity. The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation is one of the ways Indigenous people in Canada have been able to make these dark truths about Residential "Schools" heard and for people to understand the horrors these children and their parents when through.

* The reason I put quotations around the word "schools" is because these were not places of education like colonial settlers knew and know schools, which as a place of learning, friendship and growth. These places were institutions, prisons and places of torture and abuse. They were horrible places that inflicted lasting trauma on generations of Indigenous people across Canada, and I believe the word "School" is the wrong term that should be used. It allows a colonial idea of the word school to be seen in the mind's eye and does not give a true picture of what these places were like.

Please take the time to learn about survivors’ stories and the dark truths they share so that this NEVER is allowed to happen in Canada again!

Residential School Denialism is on the Rise

Canadian Museum for Human Rights - Residential School Survivors' Stories

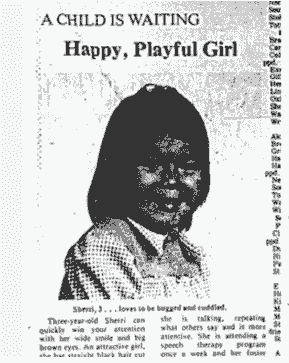

The 60's Scoop

Between approximately 1951 and 1984, an estimated 20,000 or more First Nations, Métis and Inuit infants and children were taken from their families by child welfare authorities and placed for adoption in mostly non-Indigenous households. This mass removal of Indigenous children from their homes, supported by a series of government policies, became known as the ‘Sixties Scoop’.

Historically, Indian agents used their broad administrative powers to address child welfare matters on reserve. In 1951, governments introduced new legislation to empower social workers and provincial and territorial governments with this same authority.

These children were taken from their homes, often without the consent, warning or even knowledge of the children’s families and communities. Children were adopted into predominantly non-Indigenous families, often out of province or out of the country and away from their languages, traditions and extended families. Parents and families were rarely notified about the locations of their children. Only after 1980, provincial child welfare workers informed Bands or communities of the location of children. Many families and children who were part of the Sixties Scoop are still searching for their relatives.

Today, the child welfare system in Canada is still often not able to provide adequate or safe care to children or families, especially for Indigenous children and the problem is still very prevalent in Canada today.

More information about the 60's Scoop and the lasting trauma is caused and is still causing today!

©2025 - Vancouver Island Indigenous Information - Renee Petr - All Rights Reserved