Vancouver Island Indigenous Information

- …

Vancouver Island Indigenous Information

- …

Vancouver Island Indigenous Information

Indigneous Language Revitalization

of the Languages on the

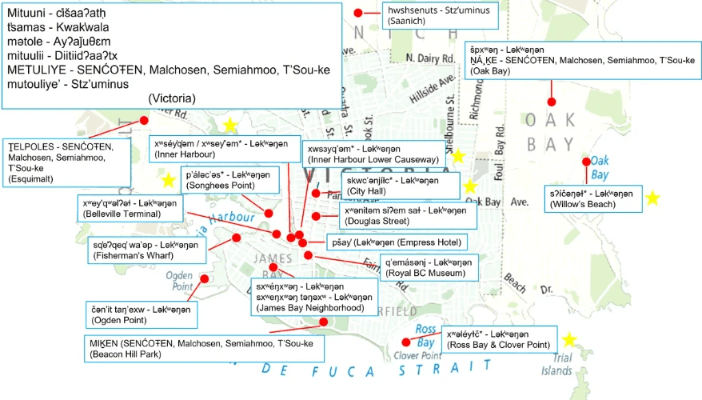

Vancouver Island Indigenous Place Names Map

Find information about the language, approximately how many speakers are left

and what language revitalization programs and language learning sites you can access.

Language Revitalization, Colonial Worldviews and Indigenous Worldviewsby Renee Petr

Since colonization, Indigenous languages have been greatly impacted, with many languages going extinct and many others being severely threatened. The reason that many Indigenous languages are not being spoken by progressive generations, is because of the Residential School System and the Canadian Government’s policy of Indigenous eradication until the 1990’s and beyond. Hundreds of years of Colonization forced Indigenous people to use English as their primary language in order to assimilate them into English, and then Canadian society. Indigenous people were severely punished and abused for speaking their languages, and when they came out of the Residential School System, they were ashamed to speak their languages or be part of their culture. This caused the vast majority of Indigenous languages to rapidly die out, as well as their culture and knowledge. To illustrate this, before colonization began, around 450 Indigenous languages were spoken across Canada, and as of 2016, only around 70 of these languages were living.

When language is destroyed, identity is destroyed, and many Indigenous cultures are still trying to come back from the legacy of colonialism. The Canadian government did everything it could to try to destroy Indigenous people, their culture, languages and worldviews, and this belief system is unfortunately still very prevalent today. Because of this attempted genocide, many Indigenous people were forced to forget their native languages and the few elders still fluent in their native Indigenous language have aged or have passed on, meaning that for lots of languages, many people can no longer speak them, or the number of speakers are dwindling. The loss of native speakers causes the languages and their meanings to be lost, and without fluent Indigenous language teachers to pass language onto the younger generations, the languages are dying out.

Thankfully, the younger generations of Indigenous people have begun to start language revitalization projects, in order to help save their endangered languages and cultures. By revitalizing these languages, they are trying to reclaim their culture, identity and worldview.

Information about Indigenous Languages found on the Vancouver Island Indigenous Place Names Brochure

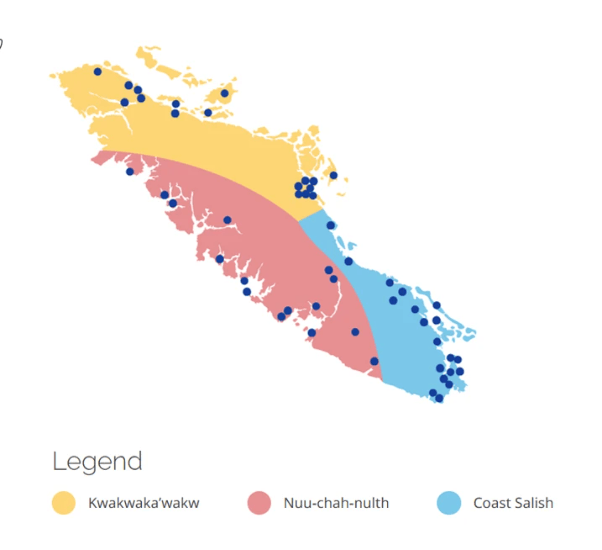

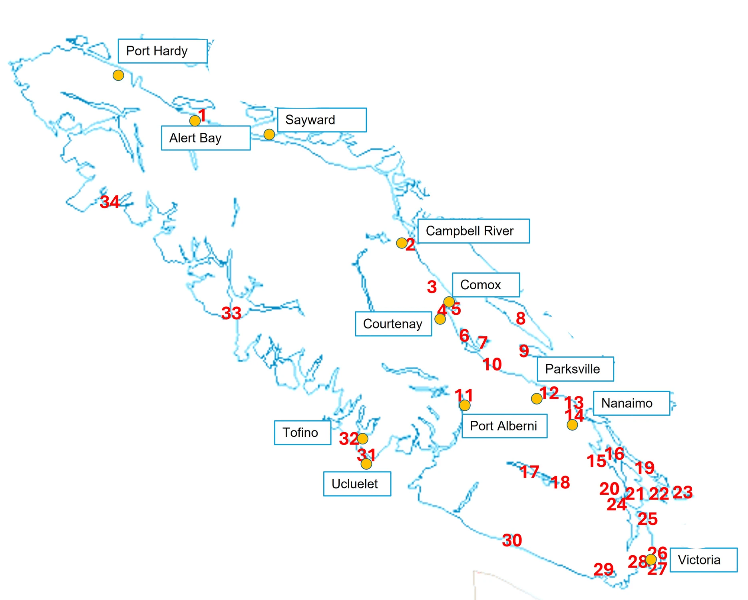

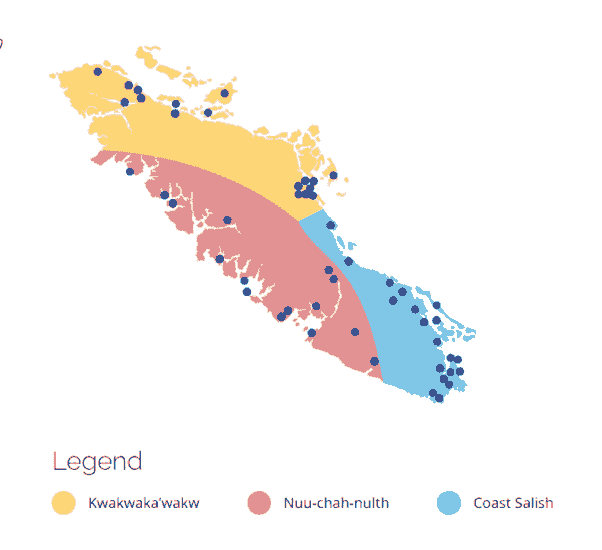

There are around eight Indigenous Languages spoken on Vancouver Island, by the many different First Nations groups that are indigenous to Vancouver Island. All of these languages are part of the Salishan and Wakashan language families, and are spoken in Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, or Coast Salish communities.

The Salishan languages spoken on Vancouver Island are mainly spoken by First Nations people in the Coast Salish region, except for two First Nations groups in the Kwakwaka’wakw area, and the Homalco and Klahoose First Nations people, which both speak languages in the Salishan language family.

The Salishan Language family includes:

- ʔayʔaǰuθəm

- Hul'q'umi'num

- Stz’uminus

- Pentl'ach

- SENĆOŦEN

- Malchosen

- Semiahmoo

- T’Sou-ke

- Lək̓ʷəŋən

Images below are sources from this Site

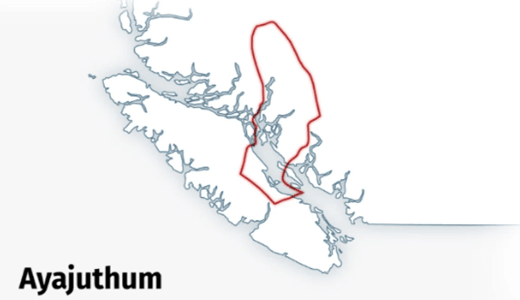

ʔayʔaǰuθəm (Ayajuthem) Language Revitalization

ʔayʔaǰuθəm “eye-ah-jew-thum”

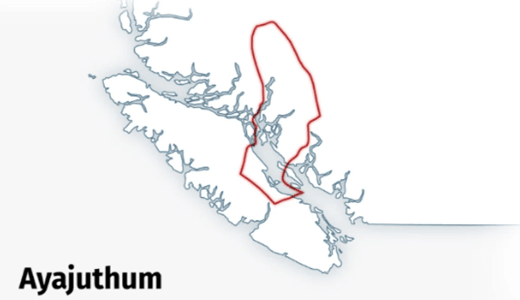

Ayajuthem, also spelled ʔayʔaǰuθəm, is spoken by the Homalco, Klahoose, K’omoks and Tla’amin First Nations. It is a Coast Salish language, specifically a northern dialect within that family. The language territory encompasses a vast area of deep forests, waters, fjords, and snowy mountain tops, including parts of upper Vancouver Island, the Comox Valley, Campbell River, and Powell River. Specifically, it includes the traditional territories of the four Nations, stretching from Hornby Island and north to Call Inlet, including Campbell River, and extending up Bute and Toba Inlets.

The ʔayʔaǰuθəm language has two dialects, ʔayʔaǰuθəm, the mainland dialect, and ʔayʔaǰusəm, the Island dialect. Homalco, Klahoose and Tla’amin Nations all speak the mainland dialect, as their traditional territory is not on the Island. The K’omoks First Nation, however, traditionally spoke ʔayʔaǰusəm, the Island dialect, as well as Pentl'ach and neighboring languages such as Kwak̓wala.

What is being done to Revitalize this language?

The ʔayʔaǰuθəm dialect was at one point lost, with the last fluent speaker passing in the 1990’s. But the language has been undergoing revitalization since the 1970's and there are now around 78 fluent speakers of the language.

Language Revitalization Programs

- The Quathet School District in part with the Tla'amin Nation Education Department in Powell River has created a ʔayʔaǰuθəm (Ayajuthem) Immersion program for preschool, Kindergarten and Grade 1 classes, in their elementary schools. The "program is called qaymɩxʷqɛnəmšt [qay-mixw qeh-numsht]. This means we will all speak our language." Pilot program is available to all students with ʔayʔaǰuθəm speaking ancestry and it is fully immersion with no english spoken during learning time. You can learn more about the program Here.

- The Raven radio 100.7 FM, Country Music radio station on Vancouver Island breathes life across Ayajuthem-speaking territory, connecting communities, youth and Elders. It has the ‘Ayajuthem Word of The Day’ program every day, several times a day, where it showcases an Ayajuthem word. Learn more about the Word of the Day Here.

- The Xwémalhkwu First Nation (HFN) is thrilled to announce the book launch for “Xwémalhkwu Hero Stories: A Graphic Novel”. Xwémalhkwu Hero Stories is based on recordings of Homalco Elders from the early 90’s that were then produced into a mini podcast series by 100.7 FM the Raven. The three stories illustrated in the graphic novel depict historic moments of Coast Salish history. Indigenous graphic artists who are featured include: Alina Pete, Valen Onstine and Gord Hill. Any individual or organization interested in purchasing the book is asked to reach out to the Homalco First Nation directly.

- North Island College (NIC) every few years offers an Ayajuthem Speaking Course that you can take at the college, which included learning circles with Elders.

- First Voices website offers words and the audio clips of ʔayʔaǰuθəm words being spoken.

Pentl'ach "punt-lutch" Language Revitalization

The Pentl'ach language is spoken by two First Nations, the Qualicum First Nation, located near Qualicum Beach, and the K’omoks First Nation.

What is being done to Revitalize this language?

This language has no fluent speakers left and is in the process of revitalization, after being declared “extinct” in the 1940’s. Eighty years after the last fluent speaker of the Pentl’ach language passed away, the Qualicum First Nation members are piecing the language together from documents, in order to bring it back from the brink or extinction. The language was one of three First Nations languages in B.C. considered “sleeping,” meaning there was no active use or learning of the language. After several years working to reconstruct the language, it is now considered by the province as a living language, because it’s actively being used and learned in the community. There are now two semi-speakers of the language and about 20 people learning Pentl’ach (pronounced punt-lutch).

Reconstructing the Pentl'ach language without any speakers posed a challenge for the Nation. All they had was a limited dictionary of translations between English and Pentl’ach, and German and Pentl’ach, and six stories written each in Pentl’ach and in German. A small team used those documents to identify some words and establish patterns of root words and prefixes and suffixes to reconstruct other words. They also looked at similar languages to find patterns. One of the similar languages used was ʔayʔaǰuθəm because pentl'ach and ʔayʔaǰuθəm place names are very similar, with the only difference being the spelling.

Language Revitalization Programs

- Pentl’ach - Reawakening the Language - online dictionary

Hul'q'umi'num "hul k umi num" Language Revitalization

Hul'q'umi'num', also known as Island Halkomelem, is a Coast Salish language spoken by First Nations on the east coast of Vancouver Island. It is one of three branches of the Halkomelem language family, with the other two being hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ (Down river dialect) and Halq'eméylem (Upriver dialect). Hul'q'umi'num' is spoken from Malahat to Nanoose Bay, with some dialectal variations.

The Hul'q'umi'num language has three dialects, Upriver Halq̓eméylem, Dow nriver hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, Island Hul'q'umi'num. Island Hul'q'umi'num is spoken by all of these First Nations.It is spoken by the Hul'q'umi'num' Mustimuhw (Hul'q'umi'num' Treaty Group), which includes various First Nations. The Hul'q'umi'num' Treaty Group represents six First Nations: Cowichan Tribes, Stz'uminus First Nation, Penelakut Tribe, Lyackson First Nation, Halalt First Nation, and Lake Cowichan First Nation. The Hul'q'umi'num' people are a Coast Salish group residing in the southeastern Vancouver Island, Gulf Islands, and Lower Fraser River regions of British Columbia, Canada. The language is currently undergoing revitalization.

Language Revitalization Programs

Community-Based Programs:

Cowichan Tribes is actively involved in language revitalization through their Dictionary Project, community language classes, and increasing the number of Hul'q'umi'num' teachers and speakers.

Language Immersion:

The Cowichan Valley School District is incorporating Hul'q'umi'num' into schools through language nests and immersion programs, including a Junior Kindergarten class at Lelum'uy'lh Daycare Centre and continuing into Kindergarten and Grade 1.

Digital Resources:

An app called Ilhe Qwal (Let's Talk), developed by Kw'umut Lelum in partnership with Ogoki Learning Inc., provides an immersive and interactive way to learn Hul'q'umi'num'.

Theatre and Storytelling:

Royal Roads University is using theatre to bring Hul'q'umi'num' stories to life, engaging learners and the wider community.

Documentation and Research:

The University of Victoria is working on developing specialized tools, like listening quizzes, to help learners and instructors assess pronunciation and identify areas of difficulty.

Language Learning sites:

o Hul’q’umi’num’ Language Academy

o First Voices Hul'q'umi'num' offers words and the audio clips of Hul'q'umi'num' words being spoken.

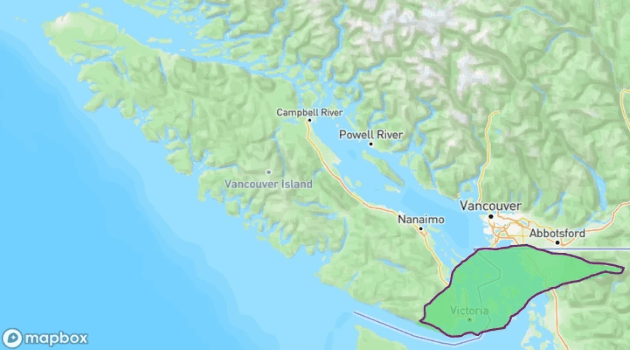

SENĆOŦEN, Malchosen, Semiahmoo, T’Sou-ke "sen cho then"

Language Revitalization

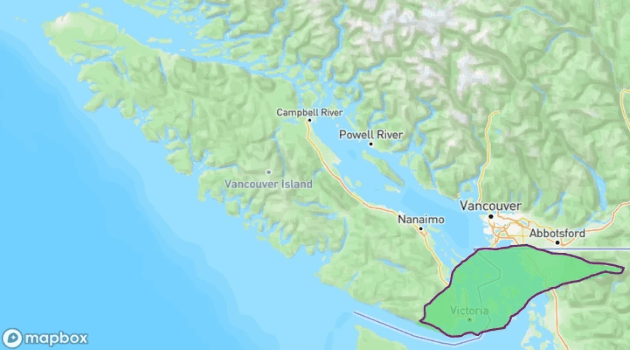

The SENĆOŦEN language has many names, depending on the First Nation that speaks it. In the different Saanich dialects, the language can be called SENĆOŦEN, Malchosen, Semiahmoo, T’Sou-ke, or Lək̓ʷəŋən. Although these are all dialects of the same language, they are also called separate languages. To describe the overall language, it is called the Straits Salish language by linguists. The SENĆOŦEN nation is a term referring to the W̱SÁNEĆ (Saanich) people and their language, which is a dialect of the Northern Straits Coast Salish language. The W̱SÁNEĆ nation is comprised of five First Nations: Tsartlip, Pauquachin, Tsawout, Tseycum, and Malahat.

They are Indigenous to the Saanich Peninsula with traditional territory spanning the southern tip of Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands, and the San Juan Islands in both Canada and the United States. They are known as "saltwater people" due to their historical reliance on the sea and their use of canoes for transportation and sustenance.

What is being done to Revitalize this language?

SENĆOŦEN also the name of the unique alphabet used to write the language, created by the late Dave Elliott a member of the Tsartlip First Nation, in 1978. Malchosen, Semiahmoo, T’Sou-ke all also use this alphabet. Dave Elliott was born on the Tsartlip reserve in June 1910. Like many Saanich families of the day, he fished and traveled over the historical homeland of the Saanich. His family knew all of the places by their original SENĆOŦEN names. Then came regulations forbidding the Saanich People from fishing, hunting and food gathering over their traditional lands. Government policies of the day dictated that the families who were struggling to survive had their children taken away to residential schools. There, the Saanich children began to experience denial of the SENĆOŦEN language and culture. Over the years, this created a communication gap between those who were still at home speaking SENĆOŦEN and those who had begun to be educated and assimilated into the white education system.

In the early 1960’s, Dave Elliott became a custodian at the Tsartlip Indian Day School, attended by most of the Saanich children. Dave recognized the rapid decline in the use of SENĆOŦEN and the knowledge of the language and culture. The late Phillip Paul led an initiative to establish the Saanich Indian School Board. The SENĆOŦEN language was immediately offered as part of the curriculum of the band operated school. Realizing that without a method of recording the language it would eventually be lost,

Dave began to write down SENĆOŦEN words phonetically. He soon discovered that upon returning to read previously recorded words, he could not understand what he had written. Dave studied with a Victoria linguist, learning the International Phonetic Alphabet and other orthographies. The main difficulty with these systems was that some of the complex sounds of the SENĆOŦEN language required numerous symbols to be represented, resulting in long and complicated words.

Dave decided to devise his own alphabet, using only one letter to denote each sound. He purchased a used typewriter and set out to make the SENĆOŦEN writing system accessible to his people. During the winter of 1978 the Dave Elliott SENĆOŦEN Alphabet was created. In 1984 the Saanich Indian School Board adopted the Dave Elliott Alphabet to help preserve the SENĆOŦEN language and history. Dave Elliott’s legacy is the revitalization of the SENĆOŦEN language.

Currently there are only 7 fluent SENĆOŦEN speakers and 103 semi-speakers. Therefore, it is essential to the language’s survival that it is passed on to new generations.

Language Revitalization Programs

Curriculum Development:

The Saanich Indian School Board adopted a written alphabet for SENĆOŦEN in 1984, and the W̱SÁNEĆ School Board continues to develop and implement language learning materials.

Educational Programs:

The University of Victoria offers a Diploma in Indigenous Language Revitalization that specifically supports SENĆOŦEN learners.

In partnership with the W̱SÁNEĆ School Board, NIȽ TU,O is delighted to announce the development of two major language revitalization initiatives; The W̱SÁNEĆ values project and the development of sencoten.org; a dedicated resource for all things SENĆOŦEN. Both projects will be instrumental in supporting language carriers, and language students, as well as supporting the preservation of language and culture.

Language Learning sites:- First Voices SENĆOŦEN offers words and the audio clips of SENĆOŦEN words being spoken.

- SENĆOŦEN Language Dictionary

- First Voices SENĆOŦEN offers words and the audio clips of SENĆOŦEN words being spoken.

Kwak’wala "Kwakw-ala" Language Revitalization

Kwak’wala is comprised of several dialects, Kwak̓wala, ’Nak̓wala, Gwa’cala, G̱utsala, Liq̓ʷala and T̓łat̓łasik̓wala. Kwak̓wala is spoken by the K’omoks First Nation, as Kwak̓walawas a neighboring language, as well as the Mamalilikulla-Qwe’qwa’sot’em, Tlowitsis, Da'naxda'xw and Awaetlala, Kwikwasut’inuxw, Haxwa’mis, Gwawaenuk, ʼNa̱mǥis, Quatsino and Kwakiutl.

’Nak̓wala, Gwa’cala and G̱utsala are dialects spoken by the Gwa’sala and ‘Nakwaxda’xw First Nations. The Liq̓ʷala dialect is spoken by the Kwiakah, Wei Wai Kum and Wei Wai Kai First Nations, and the T̓łat̓łasik̓wala dialect is spoken by the Tlatlasikwala First Nation. Kwak’wala is spoken in the northern to central Vancouver Island.

Kwakwaka'wakw First Nations, also known as the Kwakiutl Nations, live primarily on the northern part of Vancouver Island, also the southeast to the middle of the island, and includes smaller islands and inlets of Smith Sound, Queen Charlotte Strait, and Johnstone Strait.

There are around 200 fluent speakers.

Language Revitalization Programs

Educational Programs:

The U'mista Language Revitalization Planning Program (LRPP) focuses on establishing an U'mista Kwak'wala University, creating an inter-generational language nest, and offering language classes.

A Culture Camp called Nawalakw in Bond Sound was launched in 2021 to revitalize the language and create a space where Kwak'wala is spoken fluently by all ages.

North Island College Kwak̓wala Courses

Language Learning sites:

- North Island College Kwak'wala Language Course

- First Voices Kwak'wala offers words and the audio clips of Kwak’wala words being spoken

Lik̓ʷala (Likwala) Language Revitalization

It is a dialect of Kwak'wala

The Lik̓ʷala language is spoken by the Liǧʷiɫdax̌w peoples, also known as the We Wai Kai and Wei Wai Kum Nations. It is a dialect of Kwakwala, a northern Wakashan language. The Wei Wai Kum First Nation in Campbell River. For thousands of years the Wei Wai Kum lived harmoniously with the lands, waters and resources throughout their territories of the southern Johnstone Straights and adjacent mainland.

The Wei Wai Kum First Nation is a part of the Liǧʷiɫdax̌w group of tribes which formerly included more commonly known: We Wai Kai, Wei Wai Kum, Walitsima / Kahkahmatsis, and Kwiakah. The Liǧʷiɫdax̌w are the southern most group of the Kwakwaka’wakw First Nations which have historically occupied the central-to-north Vancouver Island, adjacent mainland inlets (Seymour, Smith, Kingcome, Knight, and Loughborough Inlets) and inside passage areas. The Liǧʷiɫdax̌w speak a slightly different dialect (Lekwila) from the predominant Kwakwa’la of the Nations to the North.

What is being done to Revitalize this language?

Lik̓ʷala is a highly endangered language, spoken primarily by elders in a few communities on northern Vancouver Island. The language is part of the Wakashan family and is closely related to Kwak̓wala. Efforts are underway to revitalize the language, including language nests and community-based programs.

The four main Liǧʷiɫdax̌w tribes had their ownrespective areas that they would use and occupy independently, they would often at times travel together and during early times would spend the Winters together at Topaze Harbour (Tekya). The Laich-kwil-tach were notorious for waging warfare together and raiding of various Salish origin tribes to the south. In fact, it was an aggressive migration southward of the Liǧʷiɫdax̌w which displaced Salish tribes from areas of Loughborough Inlet, sites along the Johnstone Straights, Kelsey Bay, Quadra Island and Campbell River. The reasons for this southward migration of the Liǧʷiɫdax̌w are not clear but it is evident that this occurred into periods right up the mid-19th century.

Language Revitalization Programs

Educational Programs:

The Kʷak̓ʷala and Lik̓ʷala bilingual program - One of the public school districts putting in significant effort to increase access to First Nations language learning is Campbell River School District 72, home to the Kʷak̓ʷala and Lik̓ʷala bilingual kindergarten to Grade 3 program at Ripple Rock Elementary, the only bilingual First Nations language program in a B.C. public school. Finding classroom teachers fluent in the language is very difficult, with most fluent speakers past retirement age. Currently the district is pairing up fluent language and culture teachers with classroom teachers, some of whom are non-Indigenous, to teach in the bilingual program.

Language Learning sites:

- Lik̓ʷala Digital Books: A researcher from Carleton University has also been working with the Wei Wai Kum Kwiakah Treaty Society to digitize the community’s language resources, making them accessible for teachers to use.

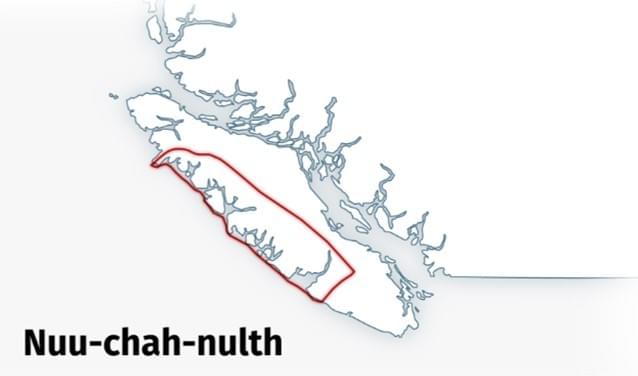

Nuu-chah-nulth (C̓išaaʔatḥ) "nuu-chah-nulth"

Language Revitalization

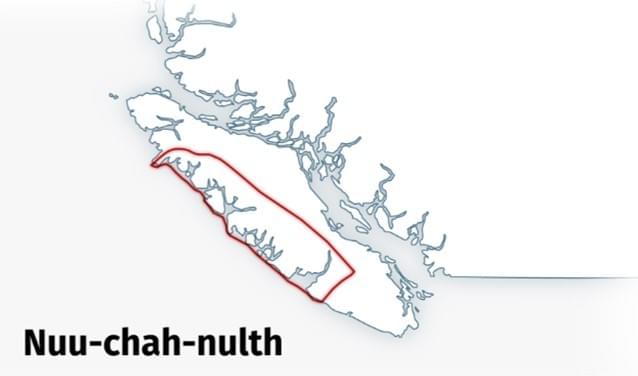

The Nuu-chah-nulth language and dialects are spoken by 14 Nuu-chah-nulth Nations in the Southern, Central and Northern regions. Therefore, the language has a large region where it is spoken, reaching down the side of Vancouver Island. The Southern First Nations include the Huu-ay-aht, in the Barkley Sound region, Bamfield and Port Alberni, and the Hupačasath in Port Alberni. This region also includes the Tse-shaht in Port Alberni and Alberni Valley, as well as on Benson Island, and the Uchucklesaht, near Port Alberni and Barkley Sound.

In the Central region are the Ahousaht, Hesquiaht, Tla-o-qui-aht, Toquaht, and Yuu-cluth-aht First Nations. The Ahousaht are located on the south eastern tip of Flores Island, and the Hesquiaht are located in Hot Springs Cove, Hesquiaht Harbour and Clayoquot Sound. The Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation are on Meares Island, as well as in Tofino and Long Beach and west of Port Alberni.

The Toquaht, or T̓uk̓ʷaaʔatḥ, are in Toquaht Bay, Mayne Bay and Western Barkley Sound, as well as Ucluelet and Port Alberni. The Yuu-cluth-aht, or Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ, First Nation is across from Ucluelet, as well as at the northern gateway to Barkley Sound. The northern region Nuu-chah-nulth Nations are Nuchatlaht, Ehattesaht/chinehkint, Kyuquot/Cheklesaht, and Mowachat/Muchalaht. The Nuchatlaht First Nation live on northern Nootka Island and the surrounding inlets, and the Ehattesaht/chinehkint First Nation lives on the Zeballos inlet.

The Kyuquot/Cheklesaht, or Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’ / Che:k:tles7et’h’, FirstNation are located in Kyuquot and Cheklesaht, and the Mowachat/Muchalaht are located in Yuquot. Nuu-chah-nulth has many dialects, but the dialect that I used on my place names map is the C̓išaaʔatḥ dialect, spoken by the Tseshaht First Nation.

Nuučaan̓uł is a southern Wakashan language spoken in the south-western section of Vancouver Island in British Columbia. It is closely related to Diidiitidq and Makah. The usual Nuučaan̓uł orthography follows the Americanist linguistics tradition, with the goal of “one letter, one sound”, including some rather complicated letters, like č̓, and some unfamiliar ones: ʕ ƛ.

The Canadian Census counts 560 people with knowledge of Nuučaan̓uł in 2016, however there are very few fluent Nuu-chah-nulth speakers left.

What is being done to Revitalize this language?

Tim Masso and Hjalmer Wenstob are brothers from the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation who have been working together to revitalize Nuu-chah-nulth through creating songs and traditional regalia and art. They spoke to the importance of uniting arts and culture with language when working towards revitalizing Indigenous languages.

Through the B.C. Language Initiative, the community has worked on Indigenous language projects such as creating a Tla-o-qui-aht language reference library, documenting language through recording, archiving and transcribing materials and creating language resources and teaching tools for the community.

A grant from the Indigenous Reconciliation Fund (IRF), helped Ahousaht Nation organized weekly ceremonies that invited cultural singers to teach songs and dances to youth and children, and build a bridge between generations.

Language Learning Resources

- Nuu-chah-nulth Language Learning Resources

- Nuu-chah-nulth Learn our Language

- Nuu-chah-nulth Phrase Book and Dictionary

- SD 70 Nuu-chah-nulth Language Learning Resource

- First Voices Nuu-chah-nulth offers words and the audio clips of kwakwala words being spoken

- Nuu-chah-nulth Language Learning Resources

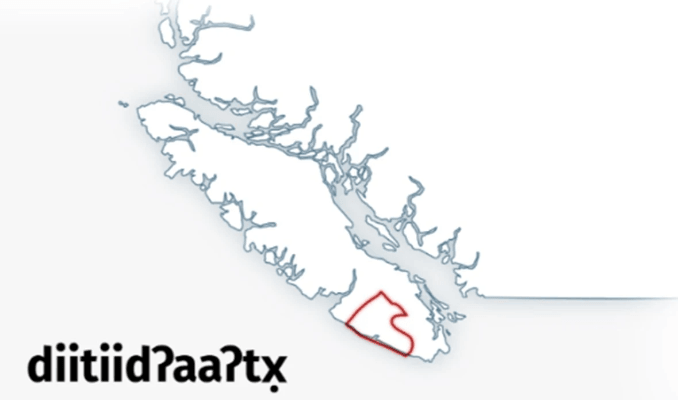

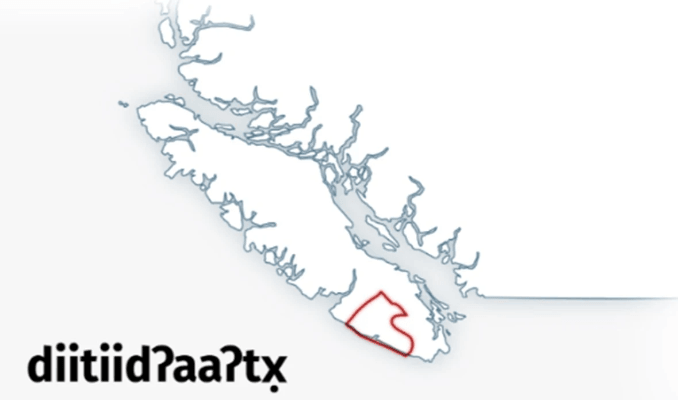

Diitiidʔaaʔtx̣ "di ti d a te"

The Diitiidʔaaʔtx̣ language, which is also spoken in the Nuu-chah-nulth speaking region, however, it is not the same language. This language is spoken by the Ditidaht and Pacheedaht First Nations. We are the Ditidaht People. We have inhabited the land around Nitinaht Lake since time immemorial. Our Ditidaht territory is large. It stretches inland to include Cowichan Lake. It reaches down Nitinaht Lake and deep into the forests. It extends along the coast between Bonilla Point and Pachena Point and encompasses a considerable distance offshore. Oral tradition indicates that at one time–some say this was before the Great Flood–the da7uu7aa7tx, the original Nitinaht people–lived in the Nitinaht Lake area.

The Pacheedaht First Nation territory reaches from Bonilla Point to Sheringham Point. Therefore, this language is spoken in the Southern Nuu-chah-nulth region, although separate. This language is also spoken on lower Vancouver Island. Nitinaht is related to the other South Wakashan languages, Makah and the neighboring Nuu-chah-nulth.

The number of native Ditidaht speakers dwindled from about thirty in the 1990's to just eight by 2006. In 2014, the number of fluent Ditidaht speakers was 7, the number of individuals who have a good grasp on the language was 6, and there were 55 people learning the language.

What is being done to Revitalize this language?

In 2003 the Ditidaht council approved construction of a $4.2 million community school to teach students on the Ditidaht (Malachan) reserve their language and culture from kindergarten to Grade 12. The program was successful in its first years and produced its first high-school graduate in 2005.

Language Learning Resources

- First Voices Diidiitidq offers words and the audio clips of Diidiitidq words being spoken

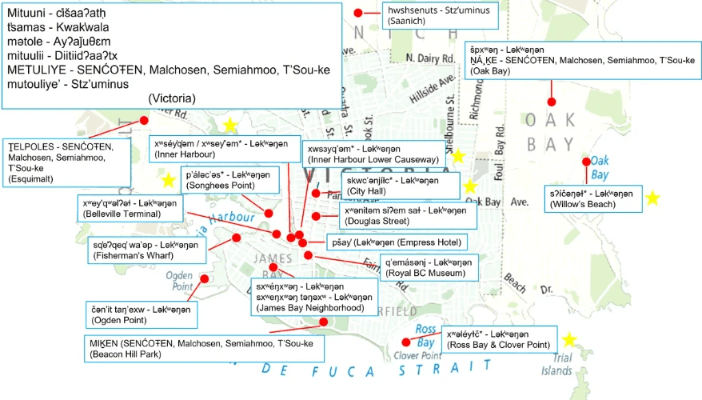

Lək̓ʷəŋən (Lekwungen) - Esquimalt and Songhees Nations

The Esquimalt Songhees Nation of the lək̓wəŋən (pronounced lekwungen) people is located beside Esquimalt and View Royal on Vancouver Island, five kilometres from Victoria. They are the descendants of the lək̓wəŋən people, original inhabitants of the Greater Victoria region. The Songhees name may come from the Lək̓wəŋən word meaning “people from scattered places”. Songhees is a Coast Salish Nation and the main language spoken historically was lək̓wəŋən people.

The Esquimalt Nation is a small nation on the water of Esquimalt Harbour. Our traditional name is Xwsepsum, also written Kosapsum.

The Victoria (Matoolia) area was divided into five territories. These lands essentially belonged to settlements that were made up of extended families. Though some overlapped in places, they were as follows: Tsuli’lhchu, around Mount Douglas (P’q’a’ls); Cheko’nein, around Cadboro Bay; Chikowetch, around Oak Bay; Swenghwung, around James Bay; and Xwsepsum (sometimes spelled Kosapsum) in what is now called Esquimalt.

Though each sche’chu (family) had its own territory, they all spoke the same language, Lekwungen. There were many families living around what is now Victoria, Esquimalt and Saanich. What is now Victoria used to be shared by five other communities: the Cheko’nein, the Chilkowetch, the Swenghwung, the Hwyuwmilth, and the Teechamitsa. They spoke the same language. lək̓ʷəŋiʔnəŋ was is a sleeping language and we are working to awaken it.

What is being done to Revitalize this language?

There is only one first language speaker of lək̓ʷəŋiʔnəŋ, who’s in his 80’s.

The Language Revitalization Program at the Songhees Nation is called həlitxʷ tθə lək̓ʷəŋiʔnəŋ“ Bringing lək̓ʷəŋiʔnəŋ Language Back to Life”.

Language Learning Resources

The Songhees Nation hosts several classes at the Songhees Wellness Centre for Community Members, Songhees Nation Staff, Preschool Students, k̓ʷam k̓ʷəm éʔləŋ / After School Program and Chief and Council, which are open to Nation Members and Staff.

NIL TU,O Child and Family Services Society - Language Learning Site

First Voices lək̓wəŋən offers words and the audio clips of lək̓wəŋən words being spoken

Scia’new and Stz’uminus First Nations - Hul'q'umi'num Language

The Scia’new First Nation is in East Sooke at Beecher Bay. The Stz’uminus First Nation’s traditional territory reached from the Strait of Georgia to Ladysmith. Our traditional territory on east Vancouver Island includes four reserves of more than 1,200 hectares, much of it bordering the Strait of Georgia and Ladysmith Harbour.

Currently the Halq'eméylem language is very close to extinction. There are probably less than 5 fluent speakers of the Upriver dialect left, and all of them are of an advanced age. No program, for this or any of the other dialects has yet succeeded in producing fluent speakers in younger generations.

What is being done to Revitalize this language?

Halq'eméylem, hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, Hul’q’umi’num’ Halq'eméylem language revitalization efforts focus on reviving and strengthening the Halq'eméylem language, spoken by the Stó:lō people in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia.

These efforts involve language learning programs, community engagement, and cultural preservation initiatives. Organizations like the University of the Fraser Valley and FirstVoices play a key role in these initiatives by providing resources, education, and opportunities for language speakers and learners.The University of the Fraser Valley offers graduate programs and courses in Halq'eméylem, including a graduate certificate, focusing on language acquisition, revitalization strategies, and cultural understanding. These programs aim to develop fluency and proficiency in the language, as well as skills for transmitting knowledge and culture.

Language Learning Resources

First Voices Halq'eméylem : offers words and the audio clips of Halq'eméylem words being spoken.

©2025 - Vancouver Island Indigenous Information - Renee Petr - All Rights Reserved