Vancouver Island Indigenous Information

- …

Vancouver Island Indigenous Information

- …

Vancouver Island Indigenous Information

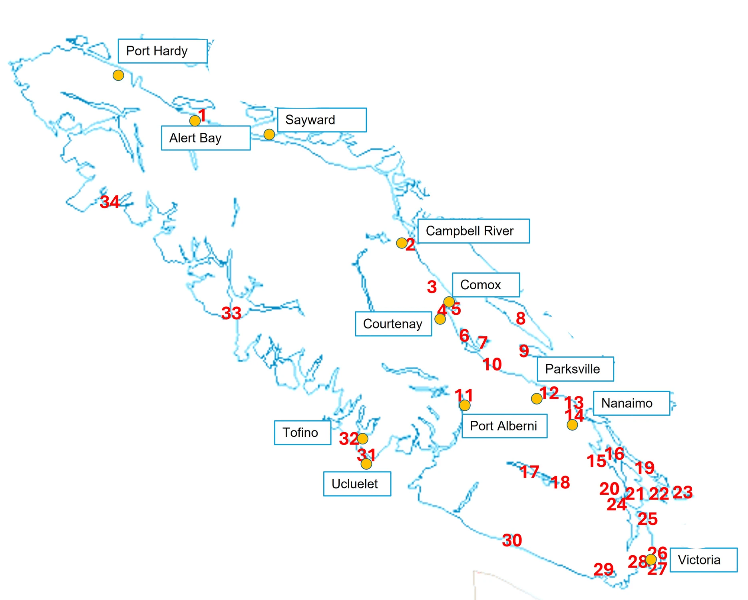

Learning about Indigenous Cultures that are

on the Vancouver Island Place Names Brochure

K'omoks First Nation

The K’omoks First Nation is a part of the Coast Salish cultural group, and a sister nation to the ɬaʔamɩn (Tla’amin), χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco), and ƛoʔos (Klahoose) First Nations, who have traditionally shared a similar culture and spoke the same language. However, the ƛoʔos (Klahoose), ɬaʔamɩn (Tla’amin) and χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) First Nations speak the mainland dialect, ʔayʔaǰuθəm, and the K’omoks First Nation traditionally spoke the Island Dialect, ʔayʔaǰusəm. The word K’omoks comes from the Lik’wala dialect of Kwak’wala, from the word Kw’umuxw, meaning “plentiful”, sometimes referred to as “the land of plenty”, due to the abundance of the land. The K’omoks people today are comprised of several Coast Salish peoples who all traditionally spoke ʔayʔaǰusəm, which include the Saɬuɬtxʷ (Sathloot), Sasitla, Ieeksen and Xa'xe, as well as the Pentl’ach speaking Pentl’ach peoples, and the Ligʷiłdaxʷ people who more recently came down into the area. Due to this, the K’omoks culture includes both Coast Salish and Kwak’waka’wakw cultural aspects, and today speak the Kwak’wala language, specifically the Lik’wala dialect.

The traditional territory of the K’omoks First Nation stretches from Kelsey Bay down to Hornby and Denman Island, including the lands around Comox and Courtenay. Historically the area of Comox and Courtenay was primarily inhabited by the Pentl’ach people, but after the Ligʷiłdaxʷ pushed southwards the K’omoks people were pushed into the Pentl’ach territory. None of the K’omoks traditional territory was ever ceded, making it unceded land. This traditional territory sustained the K’omoks peoples for thousands and thousands of years, providing an abundance of resources for all aspects of life. Salmon, shellfish, herring, deer, elk, seal, cod, rockfish, geese, duck, berries, and many different medicinal plants such as red cedar, Oregon grape, fiddlehead ferns, devils club, and many more, provided medicine and sustenance.

The K’omoks First Nations history goes back thousands and thousands of years, since time immemorial. One example of this history, going back 11,500 years ago, is the Great Flood. The K’omoks people today are descended from the survivors of this natural disaster, who survived by tying their canoes to the mountain. During this natural disaster, the rising water levels lifted the Comox Glacier up, which caused it to float up from the mountain, which then resettled down after the flood. This historic story is an important part of the K’omoks culture, with the “white whale” appearing in their logo, which is also painted on their big house. Another part of K’omoks history that is visible today can be found in the Comox Harbour and Courtenay Estuary. The Pentl’ach people, who make up a part of K’omoks ancestry, created incredibly large-scale fishing weirs that caught fish for their own community and for trading, and the wooden stakes that made up these weirs can still be seen today. In addition, some of the panel pieces have also been found, which show the skilled craftsmanship of the people.

ƛoʔos (Klahoose) First Nation

The ƛoʔos (Klahoose) First Nation is a part of the Coast Salish cultural group, and a sister nation to the ɬaʔamɩn (Tla’amin), χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco), and K’omoks First Nations, who have traditionally shared a similar culture and spoke the same language. However, the ƛoʔos (Klahoose), ɬaʔamɩn (Tla’amin) and χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) First Nations speak the mainland dialect, ʔayʔaǰuθəm, and the K’omoks First Nation traditionally spoke the Island Dialect, ʔayʔaǰusəm. The word “ƛoʔos” means “sculpin fish” in ʔayʔaǰuθəm.

The traditional territory of the ƛoʔos (Klahoose) people expands from Cortes Island to yɛkʷamɛn, (Toba Inlet), and the main village being is located at t̓oq̓ (Squirrel Cove). The traditional ƛoʔos (Klahoose) territory is all unceded land.

The canoe was and is a very important part of their culture, historically being an important part of everyday life, as travel throughout the territory by water was very important, and therefore the canoe was essential, and today is an important cultural symbol and art form.

χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) First Nation

The χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) First Nation is a part of the Coast Salish cultural group, and a sister nation to the ɬaʔamɩn (Tla’amin), ƛoʔos (Klahoose), and K’omoks First Nations, who have traditionally shared a similar culture and spoke the same language. However, the ƛoʔos (Klahoose), ɬaʔamɩn (Tla’amin) and χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) First Nations speak the mainland dialect, ʔayʔaǰuθəm, and the K’omoks First Nation traditionally spoke the Island Dialect, ʔayʔaǰusəm. The word “χʷɛmaɬkʷu” means “people of the fast-running waters” in ʔayʔaǰuθəm. This word refers to the landscapes found throughout the χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) territory, such as rapids and fast-running rivers.

The χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) territory extends from Hornby Island, across to Vancouver Island from Comox to Sayward, as well as to Call Inlet, across to the Discover Islands, from East Redonda Island, reaching up to Brem River from Toba Inlet, and reaching to Tatlayoko Lake from Bute Inlet. The main reserve today is located in Campbell River, which is within the χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) traditional territory. None of the χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) territory was ever ceded, making it unceded land.

The χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) First Nation today are descendants of those who survived the Great Flood, which is an important event in their history, and the history of the West Coast of Turtle Island. The χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) people who lived through this time survived by tying their canoes to the top of Paʔɬmɩn̓ (Estero Peak) with cedar rope, which ensured that the canoes didn’t float away as the water levels rose. Paʔɬmɩn̓ in ʔayʔaǰuθəm means “place that grows”.

Before colonization, the χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) people lived throughout their traditional territory in several villages. During the winter the people lived in permanent villages, though during the other seasons they travelled throughout the territory, following the food sources available during different times of the year, living at many temporary camps. The winter villages were located on Sonora Island at the Aaron rapids and Mushkin Village, as well as at the mouth of Bute Inlet, at ʔop̓ (Church House).

Today, the χʷɛmaɬkʷu (Homalco) live in Campbell River alongside several other nations, who are all Ligʷiłdaxʷ. The Ligʷiłdaxʷ peoples traditional territory, was historically further up Island, and only relatively recently have moved down to Campbell River and southward to Comox. This push downwards displaced Coastal Salish peoples further southward, such as the K’omoks and Pentl’ach peoples, and introduced the Kwak’wala language, which today has replaced ʔayʔaǰusəm as the language spoken by the K’omoks peoples.

Snaw’naw’as (Snaw-naw-as) First Nation

The Snaw’naw’as (Snaw-naw-as) First Nation, also known as the Nanoose First Nation, is a part of the Coast Salish cultural group, specifically the Hul’q’umi’num cultural group, sharing ancestry with the Snuneymuxw, Ts'uubaa-asatx (Lake Cowichan), Xeláltxw (Halalt), Leey'qsun (Lyackson), Spune'luxutth' (Penelakut), Stz’uminus, and Quw’utsun (Cowichan Tribes) First Nations. The Snaw’naw’as people as a part of the Hul’q’umi’num’ cultural group speak the Hul’q’umi’num’ language, which is spoken by all of these nations. The word Snaw’naw’as comes from the name of the only survivor of a battle that occurred in the 1800’s, Snaw'naw'as Mustimuxw. The name Snaw’naw’as comes from the word “naus”, meaning “the way in the harbour”.

The Snaw’naw’as First Nation’s traditional territory included villages that dotted the areas in the mid-Island region of Vancouver Island, as well as parts of the Gulf Islands, including Lasqueti Island, Texada Island, South Thormanby Island, and across to some of the mainland, and also includes Denman Island. The Snaw’naw’as traditional territory is unceded, meaning that no treaties or agreements were made with the Canadian government, the land was stolen and the Snaw’naw’as people were forcibly removed from their traditional lands.

Snuneymuxw First Nation

The Snuneymuxw First Nation is a part of the Coast Salish cultural group, specifically the Hul’q’umi’num cultural group, sharing ancestry with the Snaw’naw’as, Ts'uubaa-asatx (Lake Cowichan), Xeláltxw (Halalt), Leey'qsun (Lyackson), Spune'luxutth' (Penelakut), Stz’uminus, and Quw’utsun (Cowichan Tribes) First Nations. The Snaw’naw’as people as a part of the Hul’q’umi’num’ cultural group speak the Hul’q’umi’num’ language, which is spoken by all of these nations.

The Snuneymuxw First Nation traditional territory includes the Nanaimo, Gabriola Island, Mudge Islands, the Nanaimo watershed, the Gulf Islands, the Fraser River, Burrard Inlet, and Howe Sound. The Snuneymuxw traditional territory is unceded land, as no treaties or agreements were made that gave away their land to the Canadian government.

One part of Snuneymuxw history during the colonization, was the signing of the Sarleguun Treaty of 1854 on December 23, between the Snuneymuxw people and the Crown. This treaty is a trade and commerce treaty, that created a promise of protection and rights for the Snuneymuxw people. This treaty created the promise that the crown would protect the rights of the Snuneymuxw people forever, allowing them to continue their traditional ways of hunting, fishing and agriculture, protect their villages and the land, by allowing coal to be shared but ensuring that the land and water would be protected to ensure the continuing health for all future generations. This treaty is legally protected by section 35 of the Constitution Act, enacted in 1982, however, was completely ignored during colonization, as their lands were stolen from them and permanently changed and altered through colonial activity and settlement, and Snuneymuxw rights were restricted through the Indian Act, which included the creation and restriction to reserves, the inhibition of cultural activities, and the removal of children to Residential Schools. This treaty was ignored by the government who signed it for years and years, until in 2021, when the Snuneymuxw First Nation and the government of Canada and B.C. signed a Memorandum of Understanding, which reassures that the treaty will be recognized and implemented. The Reconciliation Implementation Framework Agreement and the Land Transfer Agreement were also created to ensure that the government of B.C. acknowledges the rights and improves the living conditions of Snuneymuxw people, as the treaty originally promised. Further, a protocol agreement was created between the City of Nanaimo and the Snuneymuxw First Nation, in order to create a framework to work together in a cooperative and mutually beneficial way, as the treaty had laid out.

Quw’utsun (Cowichan) First Nation

The Quw’utsun (Cowichan) First Nation is part of the Coast Salish cultural group, specifically the Hul’q’umi’num cultural group, sharing ancestry with the Snaw’naw’as, Snuneymuxw, Spuneluxutth (Penelakut), Stz’uminus, Leey’qsun (Lyackson) Ts’uubaa-asatx (Lake Cowichan), and Xeláltxw (Halalt) First Nations. The Quw’utsun people as a part of the Hul’q’umi’num’ cultural group speak the Hul’q’umi’num’ language, which is spoken by all of these nations. The word “Quw’utsun” comes from “shquw'utsun”, meaning “to warm ones back in the sun”.

The traditional territory of the Quw’utsun people include Cowichan Lake, the Cowichan River drainage, the Koksilah River drainage, Maple Bay, Shawnigan Lake, southern Gulf Islands, and the south arm of the Fraser River. Quw’tsun territory is unceded territory, as no treaties or agreements were ever made with the crown. In this territory the Quw’utsun had several winter villages, including Lhumlhumuluts', Qwum'yiqun', Xinupsum, Tl'ulpalus, Xwulqw'selu, Kwa'mutsun, S'amunu, and T’aa’ka. During the summer, people moved around to follow where food was, and so had many different camps along the Fraser River, whereas winter camps stayed in one place, and were generally located in Cowichan Bay and the Cowichan Valley. One of these summer camps was located on Lulu Island at Tl’uqtinus, uprier from the mouth of the Fraser River. Camps such as this one consisted of houses made of planks bound with leather strips, which could be taken down and set up. These summer camps were populated by the Quw’utsun people and neighbouring people, who travelled in flotilla to Salmon catching located, such as Tl’uqtinus. Another located that they would travel to, to catch and dry salmon, was near Yale. In the spring the Quw’utsun people also traveled throughout their territory for food, travelling throughout the Gulf Islands before they would go to the Fraser River where their summer camps were located.

The Quw’ustun people’s territory provided them with food, shelter, medicine and clothing, and they lived with the land in a respectful way, and in a way that left little trace. One of the ways that they used the land was to fish for the salmon that spawn up the Cowichan and Koksilah rivers. The Quw’utsun people used fish weirs to gather salmon. These fish weirs were managed by and the harvest distributed by the Elders. The fishing weirs were managed so that enough salmon was provided for the people, but also ensured that it did not impact the salmon population too much, to ensure that salmon populations continued to thrive. In addition to salmon, other food sources included herring, camas, sea mammals, and berries, as well as many more.

The Quw’utsun people had at one point a population of around 15,000, and were historically the most powerful nation of Southern Coastal BC. Historically and to today, Quw’utsun rights to territory, resources, social and ceremonial privileges, are distributed based on ancestry, and certain families have since time immemorial had the rights to certain locations or practices. Historically the chiefs were hereditary chiefs, although today the chief and council are elected.

After the colonial settlers came to Canada, the traditional life and ways of the Quw’utsun people was forcibly changed through colonization. The population of the Quw’utsun people declined severally when smallpox, measles, and other diseases were brought to North America. This resulted in the loss of 90% of the Quw’utsun people, bringing a population of 15,000 to just 1,000. The Quw’utsun peoples land was stolen from them, they were forcibly put on reserves, and their children for generations were sent to Residential school, where they suffered abuse. The Quw’utsun people sent delegations to England to tell the government that the land that the settlers took was their land, they even sent a petition to the Kind of England trying to tell him the same thing, but they never got a reply from either attempt, and no changes were made. However, today the Quw’utsun Nation, along with several other Hul’q’umi’num Treaty Group Nations, are currently negotiating a treaty with he government of Canada and British Columbia, to recognize their rights to their land and to create an agreement that should have been created at the very start.

Cowichan Origin Story

W̱SÍ,ḴEM (Tseycum) First Nation

The W̱SÍ,ḴEM (Tseycum) First Nation is a part of the Coast Salish cultural group. The W̱SÍ,ḴEM First Nation speaks SENĆOŦEN, which is also spoken by the BOḰEĆEN (Pauquachin), SȾÁUTW̱ (Tsawout), W̱JOȽEȽP (Tsartlip), MÁLEXEŁ (Malahat), SO¸EȻ (T’sou-ke), and SĆIȺNEW (Scia’new) First Nations. In SENĆOŦEN, the word W̱SÍ,ḴEM means “land of clay”.

The traditional territory of the W̱SÍ,ḴEM First Nation is centred around Patricia Bay on the Saanich Peninsula, and is unceded territory, as no treaties or agreements were signed to give away land to the crown.

We are in the process of building this page . . .

Please join our newsletter to get notified when new content is loaded!

©2025 - Vancouver Island Indigenous Information - Renee Petr - All Rights Reserved