Controlled Burning - Indigenous Environmental Stewardship Practice

Written by Renee Petr

Controlledburning is another environmental stewardship practice that is increasing important today. Controlled burning was practiced by Indigenous people across Canada and the world, to ensure the health of environments such as meadows and forests. Controlled burning is an incredibly important environmental practice, and one that is necessary today to prevent future fire disasters, such as the wildfires that BC faced last summer, or the LA fires that started this January.

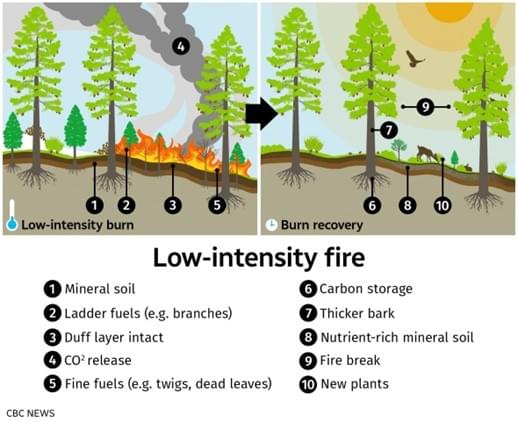

Controlledburning is the practice of burning the land with small fires, to rejuvenate the soil and prevent wildfires. Sections of land are burned at a fire with small, controlled fires, to burn away debris and ground cover. These small fires burn away ground cover and debris, but do not affect the trees, and do not have nearly the effect that large wildfires, which are caused by untended forests and lack of controlled burning, do. In these graphs, the difference between wildfires and controlled burns are illustrated.

Image: (Sködt McNalty/CBC)

Inforests, forests burn away leaf litter, dead plants and branches, which are often piled and burned. By burning this debris, it removes fuel that wildfires rely on to burn. In untended forests, this debris provides instant fuel for the fire, causing it to rapidly spread out of control. It also rejuvenates the forest environment. The fire returns nutrients into the ground, through the burned vegetation, allows more sunlight to get to the ground, creating better growing conditions for new plants, and helps plants that rely on fire to be able to spread (Controlled Burning). For example, Jack pine and Lodgepole pine trees rely on fire to open their cones, allowing them to spread their seeds. These cones, which are covered in wax, will not open without fire (Fire ecology). Controlled burns created conditions for these cones to open. These

controlled forest fires helped to reduce wildfire fuel, create better growing conditions, and increase biodiversity.

Image: (Jesse Winter)

Controlledfire was also used in grasslands, such as meadows. In these environments, fire is used to burn dead or overgrown plant materials that goes on for stretches, and could instantly catch on fire during a wildfire, as well as return nutrients to the soil to create better growing conditions. On Vancouver Island, fire was used in Garry Oak meadows, to create healthy environments, protect the Garry Oaks, and create better growing conditions for plants such as Camas. Recently I learned about how fire was specifically used in Garry Oak ecosystems by the Cowichan First Nations, in the short film “Coming Home to Grandmother’s Garden”, created by Ed Carswell. In this film, it was explained how controlled burns were used in Garry Oak ecosystems to burn debris, rejuvenate the environment, and keep invasive species and other plants from encroaching. Specifically, it was used to prevent Douglas Fir trees from taking over the environment and creating a forest. Fire was used in these ecosystems every few years during the winter, when there was the lowest fire risk, when everything had already grown, and when the nutrients in the soil where at the lowest. Fire returned nutrients to the ground through the biochar, creating better growing conditions for the Camas, Trailing Blackberries, Blackcaps and Strawberries to grow during the next year (Desbiolles et al).

Image: (Don Hankins)

Dueto being an important environmental stewardship practice, the knowledge of controlled burns, also known as prescribed fire, can be found within language. Language not only holds the knowledge of this practice, but also it’s use, and information about it, woven into the very words. I was not able to find many examples of the words for controlled burning, prescribed burning, or cultural burning in Indigenous languages in BC or across Canada, as I could only find

three, two of which included the meaning of the word, which connects to its use, practice and cultural meaning. For example, while I could not find the word in Tŝilhqot’in, the language of the Tŝilhqot’in people who live near the Chilcotin River, it has the meaning of “lightening the load off the land”, referring to the use of the fire (Boutsalis). By burning away the debris that could light on fire, posing a threat to the safety of ecosystem, as well as returning nutrients to the soil through the burns, instead of the years and years it would take through decomposition, the burning lightens the load of the land. In the Cree language, the word for fire, ‘iskotēw”, is apart of the word for women “iskwēwāk”. This connection shows the connection between women and fire. Women in many Indigenous cultures were the ones who did the traditional controlled burns, and who were in charge of fire practices. In Cree, this word shows the “important linkage between women, earth and the re-birth of land after a fire” (What Are Indigenous-Led Fire Practices?). Finally, the word for controlled burning in nsyilxcən,spoken by the Syilx, or Okanagan, people, is cikilaxwm. cikilaxwmplayed an important part in the environmental stewardship practices by the Syilx people, who live in a territory with warmer summer, creating more risk for forest fires. This is where some of the worst forest fires were last summer, during the fourth worst wildfire season in British Columbia, during which 1,680 wildfires across BC resultedin around 1.08 million hectares of land burned, destroyed forests and homes across the region (Wildfire Season Summary). Controlled burns were and still are practiced to prevent this, and need to be practiced wider across the Okanagan and BC in general, to prevent the scope and the damage of the fire season that we saw last year.

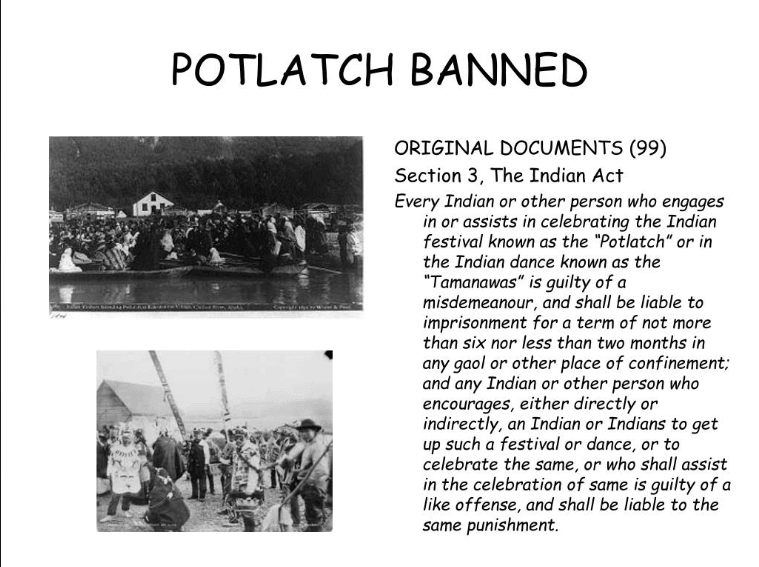

Image: (Weldon)

When the potlatch ban was put into place, controlled burns were banned, and the stigma against any fire of any sort prevented controlled burning, a necessary environmental practice, from being done. In the film “Inhabitants: An Indigenous Perspective”, created by Costa Boutsikaris and Anna Palmer, which I watched during a recent film festival where in the Comox Valley, it was explained how the Western colonists brought a mindset against any fire on the land, for any reason. The mentality was of fighting fire, not using fire to help. The creation of the Smoky Bear campaign was especially instrumental in creating this mentality, which made the public fear fire. The campaign was originally created to prevent wildfires, to prevent trees, that could be used for army efforts in World War 1, from burning. This stigma against wildfires, which can actually be beneficial in many ways, by clearing land and allowing new plants to grow, especially for those who have cones that only open in fire, has only recently begun to change in society. This means that controlled burning that only recently started to be more talked about and is now starting to be recognized for the environmental benefits that it has, and how it can help to mitigate future environmental disasters, such as the wildfires that are becoming more and more common with the warming, drought inducing, climate. The speaker gave an example of anexperiment of how language influences worldviews, to demonstrate this idea. In the experiment, it was found that speakers of both English and German viewed the same images differently, due to perspectives tied to the languages. One of my passions is language learning, and I have seen this in the different languages that I have, and I am learning. Perspective is tied to the languages that we speak, and learning languages opens up new worldviews and perspectives for us.

In the example from the video, theexperiment found that English speakers are more action-orientated, whereas German speakers needed to add a destination to the description, even if there wasn’t one show in the photograph, as the destination was more important than the action itself in their language. I have found more similar examples in the languages that I am learning. For example, English does not have as many grammatical features as Slavic languages, such as Czech, which means that it does not convey as much information, and the sentences do not need as much detail. This, combined with the action-oriented view, would create sentences that focus on a generic action. For example, in the sentence, “I’m doing homework”, the present imperfect verb “doing” only conveys an ongoing action in the present. Like the example in the video, this “doing” is usedeven if you were not presently doing homework, such as if you had been interrupted by a phone call. However, in Czech, much more information could be given to this verb, through prefixes. For example, adding one prefix to a verb would change the meaning from “I am doing homework”, to “I was doing homework earlier, then stopped for a bit, and now will finish it”. This amount of information in one word is not given in English.

Another example is in how we view theworld around us, how it interacts with us, and how we feel emotions. For example, there are two types of ways that languages express the idea of having something. One is to use a verb that means to have, which is connected to the idea of owning or possessing something, which are called habeo-languages, and the other connects more with the idea of something existing or being with or alongside you, which are called esse-languages. Some languages also use both. However, the way the language expresses this idea influences the worldview of the speaker, by creating a more inner or external view. In English, we see things as belonging to us, whereas other languages, such as Russian, Ukrainian (Ukrainian uses both) and Ayajuthem (spoken by the ΧʷɛmaɬkʷuFirst Nation in Campbell River, the ɬəʔamɛn First Nation in Port Alberni, theKlahoose First Nation in Squirrel Cove, and traditionally spoken by the K’ómoks people of the Comox Valley), use the verbs “to be”. To express this, through “(something) is at me”, is also used in Russian or Ukrainian, or as in Ayajuthem, which only uses the esse structure for the negative, such as, “there is none (of) my”.

Resources:

Cbc. “How Indigenous &Apos;Cultural Burns&Apos; Can Replenish Our Forests.” CBC, 30 Sept. 2021, www.cbc.ca/news/science/what-on-earth-indigenous-fire-forests-1.6194999.

Hankins, Don. “Reading the California Landscape for Fire - Bay Nature.” Bay Nature, 2 Feb. 2021, baynature.org/article/reading-the-landscape-for-fire.

Office national du film du Canada. “Incandescence.” Office National Du Film Du Canada, www.onf.ca/film/incandescence.

Von Handorf, Jessica. “9 Ways to Connect Climate Change to Canada’s Wildfire Story.” Re.Climate, 23 May 2025, reclimate.ca/9-ways-to-connect-climate-change-to-canadas-wildfire-story.

Weldon. “CANADA TAKES CONTROL - SlideServe.” SlideServe, 21 July 2014, www.slideserve.com/weldon/canada-takes-control#google_vignette.